Updated: Category: Cloud

Chasing Shiny Objects Makes You Blind

While most of us mortals are still busy migrating existing applications to the cloud or perhaps building new cloud-ready applications, the marketing departments haven’t been sleeping at the wheel and are touting stuff like multi-hybrid-cloud computing (or was it hybrid-multi?).

The cynic in us will quickly conclude that chasing ever more shiny objects is easier than delivering something simple, but working. So, let’s not be blindsided by the glow of new buzzwords and cut through the hype to translate the buzz into architecture insights. While some detailed articles on Multi Cloud vs Hybrid Cloud and a set of patterns from our friends at Google Cloud are helpful, they don’t quite crystallize the architectural essence of the options we have and the decisions we need to make.

Hence, it’s useful to take the point of view of an architect who rides the Architect Elevator: what key decisions, constraints, and assumptions are baked into the solutions? What options do you have and what decisions do you need to make? What are each option’s benefits and costs, both in Dollars but also in complexity and lock-in? Let’s go have a look!

Hybrid is a Reality. Multi-cloud is an option.

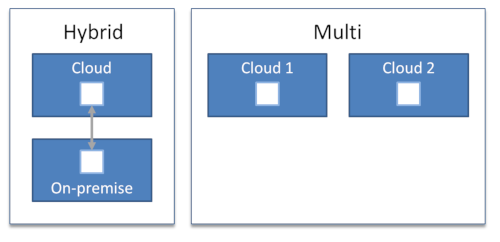

First, let’s segregate hybrid from multi. As easy as this may seem, one already encounters a reasonable amount of confusion and conflicting definitions. Let’s start very simple:

- hybrid: splitting workload(s) across the cloud and on-premise. Generally, these workloads pertain to a single application, meaning the piece in the cloud and the piece on-premise interact to do something useful.

- multi: running workloads with more than one cloud provider. If we get more precise than that, opinions diverge.

Now some folks, including GCP, consider on-premises to be part of multi-cloud (“A multi-cloud setup might also include private computing environments”). While technically the two are surely related (“on-prem is just another data center”) if you count hybrid into multi, then there wouldn’t be any need to use the term multi-hybrid. Already confused? Let’s look at things from a different angle.

“No CIO will wake up one morning to find all of his or her workloads in the cloud. Hybrid cloud is a reality.”

Whatever the technology, the intentions and drivers behind hybrid and multi are quite different. Hybrid cloud is a reality for enterprises: despite cool stuff like AWS Snowmobile no CIO will wake up one morning to find all of his or her workloads in the cloud. So, you’re bound to have something “out” and something still “in”, and the two more likely than not need to interact.

Hence, the core of a hybrid cloud strategy is “how to slice”, i.e. what workloads should move out while which other ones stay on premises. This topic is important enough to deserve a post of its own.

“A hybrid cloud strategy’s essence is deciding how to slice, i.e. what workloads should move out and which other ones stay on premises”.

In contrast, a multi-cloud strategy is an architecture choice you make. Examining common multi-cloud approaches and the motivations behind them helps us make these choices.

Dissecting Multi-cloud

To better understand the motivation for multi-cloud, it’s good to segment the technical platform architecture into common scenarios. What I have observed as packaged under the slogan of “multi-cloud” generally falls into one of the following categories:

A higher number isn’t necessarily better in this comparison - it’s about finding the approach that best suits your needs and making a conscious choice.

“Multi-cloud isn’t a black-or white choice nor a one-size fits all architecture.”

Let’s look at each option in more detail.

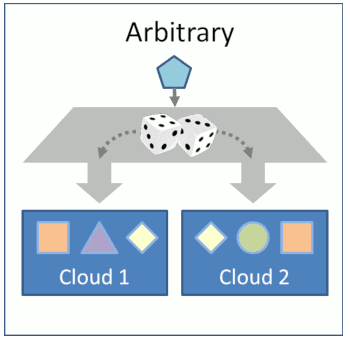

Arbitrary

If enterprise has taught us one thing, it’s likely that reality rarely lives up to the slide decks. Applying this line of reasoning (and the usual dosage of cynicism) to multi-cloud, we find that a huge percentage of enterprise multi-cloud is the result of poor governance and excessive vendor influence. It basically means that you have some workloads running in the orange cloud, some others in the light blue cloud, and a few more under the rainbow. You don’t have much of an idea why things are in one cloud or the other, or, more likely, you started with orange, then you received a huge credit from light blue thanks to existing license agreements, and some of the cool kids love the rainbow stuff. And if you look carefully, you may see some red peeking in due to personal relationships and a heavy sales push.

Strategy isn’t exactly the word to be used for this multi-cloud setup. It’s not all bad, though: at least you are deploying something to the cloud! That’s a good thing because before you can steer you first have to move. So, at least you’re moving. This also means you are gathering experience and building skill set with multiple technology platforms, that is unless you outsourced thinking.

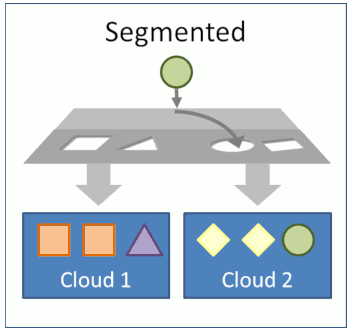

Segmented

Segmenting workloads across different clouds is also common, and a good step ahead: you deploy specific types of workload to specific clouds.

This scenario often results from different vendor preferences for different kind of workloads, for example due to individual vendors’ strengths or licensing terms. A common combination is to have most workloads in orange, Windows-related workloads on light blue, and ML/analytics on rainbow, even though the vendor capabilities are rapidly shifting in the latter category.

You may decide to segregate by a number of factors:

- Type of workload (legacy or modern)

- Type of data (confidential vs. open)

- Type of product (compute vs. data analytics vs. collaboration software)

When pursuing this approach, it’s helpful to understand the seams between your applications so you don’t incur excessive egress charges because half your application ends up left and the other half on the right.

Also, I have observed enterprises slipping from segmentation back into arbitrary due to vendor affinity. You may use cloud vendor X for a specific type of service, but their (pre-)sales folks will likely convince teams to use their other services as well. That’s their job, so you need to decide where you want to head. If you don’t, you end up in situations like (a real example) running 95% of your compute on ECS in Singapore but some on AppEngine in Tokyo, which makes little sense.

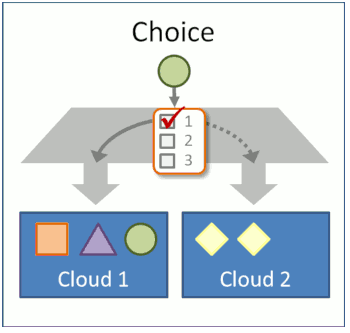

Choice

Many might not consider the first two examples as true multi cloud. What they are looking for (and pitching) is being able to deploy workloads freely across cloud providers, thus minimizing lock-in (or the perception thereof), usually by means of adding abstraction layers. This ambition again breaks down into multiple flavors, the less complex and more common case allowing an initial choice of cloud platform, with the assumption that you don’t keep changing your mind.

This choice scenario is common for large organizations’ shared IT providers because they are expected to support a wide range of business units and their respective IT preferences. Often, such a setup involves a central commercial relationship and a common framework to create instances on the cloud provider of your choice but with corporate governance and constraints tacked on.

The advantage of this setup is that projects are free to use proprietary cloud services, such as managed databases (depending on their preferred trade-off between avoiding lock-in and minimizing operational overhead). Hence, this setup makes a good initial step for multi-cloud.

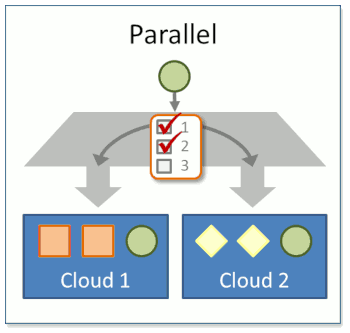

Parallel

While the previous option gives you a choice among cloud service providers, you are still bound by the service level of a single provider. Many enterprises are looking to deploy critical applications across multiple clouds to assure higher levels of availability than they could achieve with a single provider, even with that provider’s multiple availability zones.

Being able to deploy the same application into multiple clouds requires a certain set of decoupling from the cloud provider’s proprietary features. This can be achieved in a number of ways, for example:

- Managing cloud-specific functions such as identity management, deployment automation, or monitoring separate from the application in a cloud-specific manner

- Using open source components as much as possible - they will generally run on any cloud. While this works relatively well for pure compute (hosted Kubernetes is available on most clouds), it may reduce your ability to take advantage of other fully managed services, such as data stores or monitoring. Because managed services are one of the key benefits of moving to the clouds, you need to consider your options carefully.

- Utilize a multi-cloud abstraction framework, so you can develop once and deploy to any cloud.

- Maintain two branches for those components of your application that are cloud provider specific and wrap them behind a common interface. For example, you could have a common interface for block data storage.

While the latter sounds kludgy, it’s what we have been doing with databases and many other dependencies for a while. Properly wrapped, it’s a viable option.

The key aspect to watch out for is complexity, which can easily undo the anticipated uptime gain. Additional layers of abstraction and more tooling also increase the chance of a misconfiguration. Also, if you deploy a broken application to both clouds, then you will still suffer downtime, so make sure to account for human error. I have seen vendors suggesting designs that deploy across each vendor’s three availability zones, plus a disaster recovery environment in each, times three cloud providers. So, one component occupies 3 * 2 * 3 = 18 nodes - I’d be skeptical whether this amount of machinery really gives you higher availability than using 9 nodes (one per zone and per cloud provider).

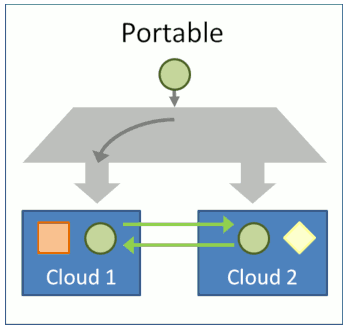

Portable

The perceived pinnacle of multi-cloud is free portability across clouds, meaning you can deploy your workloads anywhere and also move them as you please. The advantages are easy to grasp: you can avoid vendor lock-in, which for example gives you negotiation power. You can also move applications based on resource needs. For example, you may run normal operations in one cloud and burst excessive traffic into another.

The mechanism to enable this capability is high levels of automation and abstraction away from cloud services. While for parallel deployments you could get away with a semi-manual setup or deployment process, full portability requires you to be able to shift the workload any time, so everything better be fully automated.

Multi-cloud abstraction frameworks such as Anthos promise to make this type of setup easy. However, nothing is ever free, so the cost comes in form of lock-in o a specific vendor, product, and architecture plus a requirement to deploy the application in containers. Also, such abstractions generally don’t take care of your data: if you shift your compute nodes across providers willy-nilly, how are you going to keep your data in sync? And if you manage to overcome this hurdle, egress data costs may come to nib you in the rear.

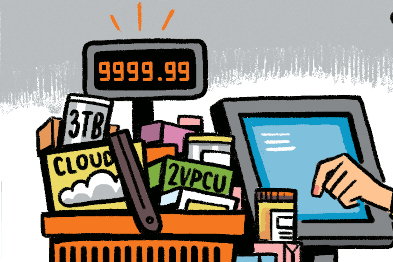

Polishing Your Shiny Object

When chasing shiny objects, we can easily fall into the trap of thinking that the shinier, the better. Those with enterprise battle scars know all to well that polishing objects to become ever more shiny comes at a cost. Dollar cost is the apparent concern, but you also need to factor in additional complexity, having to manage multiple vendors, finding the right skill set, and long-term viability (will we ditch all this container stuff and go serverless?). Those factors can’t be solved with money.

It’s therefore paramount to understand and clearly communicate your primary objective. Are you looking at multi-cloud so you can better negotiate with vendors, to increase your availability, or to support deploying in regions where only one provider or the other may have a data center? Remember, that “avoiding lock-in” is only a meta-goal, which, while architecturally desirable, needs to be justified by a tangible benefit.

The following table summarizes the choices, the main drivers, and the side-effects to watch out for:

| Style | Key Capability | Key Mechanism | Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arbitrary | Deploying applications to the cloud. | Cloud skill | Lack of governance. Network traffic cost. |

| Segmented | Clear guidance on cloud usage. | Governance | Vendors may steer you back to “Arbitrary”. |

| Choice | Support project needs and preferences; reduce lock-in | Common framework for provisioning, billing, governance | Yet-another layer of abstraction. Lack of guidance. |

| Parallel | Higher availability than single cloud. | Automation, abstraction, load balancing. | Complexity; under-utilization of cloud services; |

| Portable | Shift workloads as you please. | Full automation, abstraction. Data portability. | Complexity; Lock-in into multi-cloud frameworks. |

As expected: TANSTAAFL - there ain’t no such a thing as a free lunch. Architecture is the business of trade-offs. Therefore, it’s important to break down the options, give them meaningful names, and understand their implications. Armed with these tools, you can happily ride the Architect Elevator and chart your course to hybrid-multi-cloud enlightenment. Of course, before moving anything to the cloud, remember not to run software you didn’t build!.

More on Cloud Architecture

A strategy doesn't come from looking for easy answers but rather from asking the right questions. Cloud Strategy, loaded with 330 pages of vendor-neutral insight, is bound to trigger many questions as it lets you look at your cloud journey from a new angle.