Updated: Category: Architecture

Architects live at the intersection of just about everything: strategy and execution, governance and innovation, transformation and stability, software design and operations. It’s no surprise, then, that it’s not easy to pin down what exactly architects do and what skills they need to have to do it well.

The human aspects of software delivery deservedly received more attention in recent years. Socio-technical became a household term, reminding us that the systems we deal with consist of both humans and machines (I am sure there is a Matrix reference in there, perhaps the Resurrection). We also learned that architects tend to carry little direct power but steer by influence, something that can only work if they are good communicators.

The ever-broadening spectrum of architecture activities (and architect personas) has also opened up the opportunity for folks to pitch that architecture is about one thing or another, when in reality it’s about many things. Here are some especially popular versions of that phenomenon:

“Enterprise Architecture is not about technology.”

It very much is about technology. The enterprise landscape that architects shape is driven by new technology and new technical capabilities. That tech becomes ever more potent but also more complex. Without understanding it, you’re just another paper-pushing manager who checks items off a work breakdown-structure. Even a business architect, which is a delicate and sometimes misunderstood role, must understanding how technology evolution impacts business models and organizational structures.

“Business drives IT.”

Yes, it does, but IT drives back. A great example is the shift from a product model to a service model, meaning that instead of shipping products, businesses charge for a service that they provide–holes instead of drills and passenger-kilometers instead of train engines. We may wonder why we didn’t implement those models 20 years ago (some consumer items like CDs did transition to music streaming over a decade ago when the required infrastructure became widely available). The answer is simple: lack of technical capabilities. Without IoT, cloud, and advanced analytics to perform predictive maintenance, those business models equate to corporate suicide: if your equipment doesn’t punch holes or move passengers, you won’t get paid. So, technology also very much drives business strategy.

“It’s all about the people.”

Yes, it is also about people. But not entirely. People, processes, and ways of working need to support each other to fully utilize new technology capabilities. Why do organizations routinely transform in the context of a cloud migration? Because the cloud enables new ways of working and only delivers the anticipated benefits if organizations adopt. So, it is about the people, but the change is driven by technological advancement.

“It’s all about business value.”

Right, but also wrong. Of course, IT work must generate value for the business. But running around touting business value is like giving career and life advice in the form of “be rich and healthy”. As so often, the destination is clear, but the path requires some consideration.

The product, not the sum

During my time in Big 4 consulting two decades ago, people, process, technology was a guiding slogan (folks still spew it out like it’s a novelty). Alas, it’s just a lists of the things that we should consider. It doesn’t explain how they relate to one another. To me, that’s where architecture plays!

Effective architects don’t shift attention to one element at the expense of another. Rather, they expand their scope and connect the dots across the elements. This makes for a more challenging but also more impactful role. You may deal with people transformation in the morning just to tackle an operational issue in the afternoon before finishing up a strategy paper.

It’s not just a matter of adding more things to our plate. The different elements, like having good communication skills, understanding organizational dynamics, and keeping up with technology are strongly intertwined. For example, it’s not sufficient to be a good communicator and a good technologist. You have to be a good technical communicator, making complex topics approachable without dumbing them down. You have to remain engaging without drifting completely into storytelling–your job is to highlight critical technical decisions and trade-offs. That’s different from taking a wide stance, looking your audience in the eye, raising our arms for a greeting, and reciting heartwarming stories from your childhood, which is what TED talk love to do (they rarely talk about concurrency bugs or architecture strategy). A stock photo of a person at crossroads can draw attention (I frequently use them for keynotes), but it can’t describe architecture alternatives and their trade-offs.

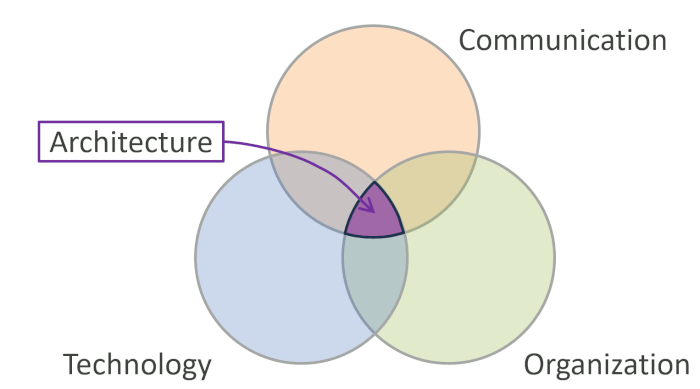

So, as architects, it’s not sufficient to possess multiple skills, you need to master the intersection between them. This means, becoming an architect is not a matter of addition, but one of force multiplication:

As the Venn diagram shows, architects live in the purple center, not in the pale crescents.

Architects are Multipliers

I routinely observe the multiplier effect in action:

Technical Presentations

Presenting technical content forms a significant part of my Architect Elevator Workshops. Yet, it’s not a usual presentation training that teaches you to have a wide stance, look people in the eye, and “tell’em what you’re gonna tell’em”. Instead, it’s about making technical decisions and trade-offs approachable and relevant to an executive audience. Interestingly, it’s not about making things simple–most strategic tech decisions aren’t simple. It’s about amplifying a core message and using metaphors to translate technical trade-offs into the audience’s domain.

We practice the balance between logos (facts and reasoning), ethos (your credibility), and pathos (believes and emotions). Most tech presentations rely almost exclusively on logos. We present facts and logic, and if the audience doesn’t bite, we spew out more facts. The goal of the exercises isn’t to give up logos, though: We still have a technical message to convey and need to get buy-in into technical trade-offs. Successful technical presentations live at the intersection of understanding technology and having good communication skills.

The same is true for visual aids. I had several instances where folks “prettify” slides and inadvertently change the message. Architects also make clear slides, but they do so to amplify the underlying model and technical message. We often iterate between choosing a model, seeing if a pattern or a punchy storyline emerges, and if not, we change the model. This process, which I call “left brain, right brain ping pong” cannot be done by a person with good technical skills paired with a graphics designer. You have to combine both skills to get the multiplies effect.

The multiplier effect happens when sharpening your storyline also sharpens your technical insight.

We observe this routinely in the workshops as a variant of my “Diagram-Driven Design” mantra: if you can’t explain it well despite multiple attempts, perhaps something’s not right with your design. If you want to see the power of skills multiplication in action, see my blog post on executive impact.

Leading Technical Teams

Leading teams also isn’t just about understanding people, process, and technology. Good technical leaders are role models, understand and value their team’s skills, or find ways to simplify designs (naturally, without micromanaging). If managers are accountable for performance evaluations and can’t judge technical skills, teams will quickly learn that they can get by with sounding smart instead of actually knowing their stuff. This is one reason why many tech companies use a peer-based review system, but believing that the manager has no influence is rather naive.

A good technical leader is a force multiplier for the teams: it makes them more productive, better decision makers, and happier. And you need to have some idea what you are managing.

Building Platforms

Platforms live at the intersection of technical and business domains. They should not second-guess cloud providers but layer services on top that incorporate industry- and company-specific aspects. To do this well, you must understand your business domain, technical platform capabilities, and how to structure a team to be customer-centric and product-oriented. But again, it’s not the simple sum of these skills, but the cross-product: shaping a layer that exposes a new domain and leverages automation, self-service, and transparency. It’s not 3 aspects stuck together, but 3 aspects intertwined.

Becoming a Force-Multiplying Architect

A lot of folks aim to become a better architect by adding skills. That’s useful, but not sufficient. In addition to adding more skills to your repertoire, successful architects synthesize the things that they learned and become a force multiplier.

Occasionally, folks propose a Pi-shaped skills profile, which derives from the T-Shape, meaning being broad but also being deep in one area. Pi-shaped people are presumed to be deep in two areas. I propose to the Pi a new connotation. The Greek letter Pi stands for product (Sigma indicates the sum), so architects are Pi-shaped by having their skills be the product of multiple skills domains.

Grow Your Impact as an Architect

The Software Architect Elevator helps architects and IT professionals to take their role to the next level. By sharing the real-life journey of a chief architect, it shows how to influence organizations at the intersection of business and technology. Buy it on Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon Europe