Updated: Category: Transformation

Architects engaging as change drivers must be prepared to face resistance. Change isn’t popular, even if people honestly believe that the end result will be positive. For most folks, things get worse before they get better: they need to learn new approaches, may be less productive initially, make more mistakes, or score lower on established performance metrics. Trying to push too much change through an organization will cost you, sometimes your job. A simple model can help you manage the amount of goodwill that you have and how to spend it in a meaningful way.

Political Capital must be earned

A common mistake is coming into an organization, seeing a lot of opportunity for improvement, and pushing hard to make things better. Although well-intentioned, this approach is unlikely to effect lasting change, and may cost the new arrival their job. Driving change requires goodwill and credibility. You are convinced that the changes you propose will improve things, but to others this may not be clear at all. In their eyes, they are taking a risk.

Ironically, most organizations that are looking to transform still do (or at least have been doing) quite well. That’s because their success bred waste, and waste attracts disruptors who operate much leaner. So, the companies most urgently looking for change are the ones who have had a lot of success doing things “the way they always were”. It’s easy to see that folks in such places have no urgency to change anything.

To drive change in such organizations requires Political Capital, an asset of goodwill, or occasional forgiveness that you can dip into. As the name suggests, the concept originates from political parties and public policy, where Pierre Bourdieu is widely credited with establishing it. We map it here to the context of bringing change into organizations.

You may arrive in an organization with some amount of upfront deposit to your Political Capital, based on your professional track record, your prior employer, or your personal brand. But that is rarely sufficient to go “big bang” on an organization, which would consume a large amount of capital. Without sufficient deposits, you will go bankrupt, which means that rather than embracing change, people may ignore, or even look to dispose of you. So, before you go and make major withdrawals, make sure you have sufficient deposits within the organization.

Your Piggy Bank for change

The metaphor I use for political capital is that of a Piggy Bank: you save slowly, but you withdraw a big chunk at once. Bursting the piggy bank is scary, but it’s the best way to drive major change. Starting small changes everywhere is likely to deplete your capital without any lasting impact. Instead, choose your battles and get ready to hit one area hard.

A complication is that you can’t know exactly how much money is in your piggy bank. So, you need to develop some heuristics for how much you need to spend, meaning how unpopular change is going to be. Making major staffing changes or completely changing the way of working is likely to cost you more than introducing a new tool.

Spend your Political Capital, but spend it wisely

Earning political capital is necessary, but the goal isn’t to get rich. Political capital is there to be spent, but in a meaningful way. Running around and telling everyone that they have been doing everything wrong and that you are here to finally enlighten them is not a meaningful way to spend political capital. That’s just being a prick.

Always be earning

To avoid going bankrupt, it’s good to always be earning political capital. Most ways of doing so are actually good things to do and the list is longer than most people initially believe:

-

Deliver: Nothing speaks louder than success. Proving that what you promise actually works and delivers the anticipated results is one of the biggest deposits that you can make to your credibility.

-

Do as you say: It’s easy to judge others by their behavior and yourself by intention. Avoid that trap and follow the guidelines that you ask others to adhere to. A classic counterexample is workplace equipment: all employees are required to have a standard laptop or phone while senior executives enjoy non-standard devices. Sounds like Animal Farm?

-

Be Transparent: If you hide (or appear to) what you are working on, or the goals that you pursue, suspicion will grow. So, you can earn capital by sharing openly. In the worst case, you may get push back or folks may misappropriate your published ideas. To me that’s still a worthwhile tradeoff for the trust you earn and the example you set.

-

Be Available: Everyone’s day has the same number of hours. So, “being busy” is a matter of setting priorities. Making time for people will earn you political capital.

-

Be Approachable: While being available translates into “the door is open”, being approachable means that “people are comfortable to walk in”.

-

Listen: It’s one of the things that’s so easy to do, yet far too often ignored. As engineers, we often jump to solutions before we even listen to the problem. That’s understandable because we are paid to provide solutions. But taking the time to listen, even if you might disagree, shows empathy and builds understanding (and helps you solve the right problem).

-

Show genuine interest, care: People can easily tell if you are interested in their work. I genuinely find all businesses interesting. It’s a big motivator for me and also earns political capital: it shows that I am seeing to understand first before giving direction.

-

Ask for help: Some approaches can be deposits and withdrawals, depending on context. Asking people for favors or for help generally uses your political capital. But asking for help can also mean that you are open for input and appreciate the expertise that other teams have. For this to work, it has to be “we are stuck on this thing that you know a lot about; could you take a look?”, not “we are busy, so could you do some of our work?”.

-

Give credit: As with so many items in this list, giving credit where credit is due costs you nothing but earns you a lot in return.

-

Own your mistakes: Vice versa, if you screwed things up, raise your hand and admit it. This way, even if you (occasionally )didn’t deliver, you can still earn trust.

-

Mentor: Share what you know, help others grow. They will appreciate you for it.

-

Keep cool under stress: A lot of good intentions fade when the pressure mounts. Keeping a clear head, setting priorities and direction instead of throwing tantrums not only makes you a better leader, it also earns political capital.

-

Be consistent: Recall that political capital is earned slowly, but spent quickly. That means that many good deeds can be eradicated by one outburst. As with many good practices, consistency is key.

I encourage you to add to the list as it’s meant to be incomplete. All items in the list are positive and cost you little.

Good intentions vs corporate politics

But good intentions can wane when you see people around you get ahead by doing the opposite of these positive patterns, for example, folks aren’t transparent because they use information to their advantage. Then, you feel like sharing openly may seem like playing into their hands. In the short-term it may, but the odds are good that you have the advantage over the long haul. Working to higher standards, for example by being transparent, can erode others’ power base over time or allow you to call out their dysfunctions. You won’t be able to change an organization if you fall into the same dysfunctions that you are looking to eliminate.

Spending with a purpose

The goal isn’t to become the most popular person in the company, although that’s certainly nice. Architects who see themselves as change agents, should feel comfortable spending their political capital when needed.

-

Bring change: Most change is unwelcome, even if it leads to improvement. Change means learning new routines, making more mistakes, or changing incentives. All this will cost you political capital.

-

Question the status quo: Driving change also raises the uncomfortable truth that things aren’t as great as assumed. Even that can cost you.

Commenting once that a fancy tech company’s internal systems aren’t all that great (Chime, Quip, or TT, anyone?), led to a peer review feedback that I need to embrace the company’s culture of self-service (ironic for a person who joined from Google, which lives self-service with much better tooling).

-

Asking favors: The obvious withdrawal is asking folks to help you out. When you’re in a pinch, you’ll be happy that you built up some capital to draw on.

-

Asking for a leap of faith: We like decisions to be data-driven, but sometimes you may want to ask your stakeholders to let you try something out or follow your hunch.

-

Ask for forgiveness: Similarly, pursuing a path with explicit permission leaves you with having to ask for forgiveness. That’ll work a lot better if you have earned capital before.

-

Optimize for the long term: bringing long-term gain at the cost of short-term pain will cost you, as reflected in my saying that the path to the mountain of gold leads through the swamp. The swamp part will cost you capital.

-

Inject yourself: something may not be in your immediate remit, but you may ask to be involved or insist that your approval is needed, for example to stem off duplication.

-

Ask for time: It may seem obvious that you shouldn’t waste people’s time. Time is the most valuable resource, so taking more time to complete a task or asking for a meeting is also a small withdrawal (sometimes I actually wish that I could charge people for setting up a meeting–it may drastically increase the meeting quality).

-

Escalate: Deferring an issue or a decision to a higher level in the organization will also cost you, even when it’s the right thing to do, for example to get a project unstuck or to resolve a stalemate. How much it’ll cost depends on the company culture. Some organizations may consider it treason whereas others like Amazon have an openly declared escalation culture.

-

“Told you so”: Telling someone that you had predicted an unfavorable outcome isn’t a meaningful withdrawal in most cases. But done in a constructive way as a postmortem, it can be.

When preparing for a sales presentation for a senior client executive, I recommended to remove one section because I expected the client to find it too strong on buzzwords and too weak on facts. The account team felt bad about uninviting the presenters, so it stayed. After the meeting, the client sent a thank you note stating that all sessions were highly informative, except the one that I had flagged, which he described as a “complete waste of time”. I did remind the team that we weren’t just unlucky because–told you so–we knew ahead of time but ignored our instinct.

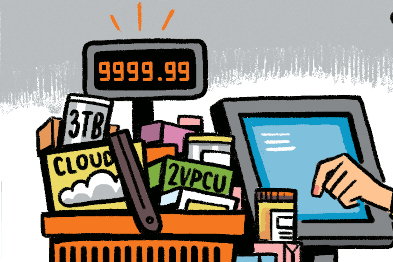

Save up to spend big

You may remember that as a kid you had to learn to save up your pocket money to buy an enjoyable toy / gadget in a month instead of candy every day. Well, you learned something for (corporate) life. Although it’s OK to make small tactical withdrawals when in a pinch, you’ll have more impact by saving up capital to make a major move when the time is right. Making it across the swamp is worth the investment, but dipping your toes into many swamps won’t get you to any mountain of gold.

The biggest withdrawal I likely made was having the architecture team operate the in-house PaaS against established processes and the desire of the ops team. The reason for the spend was that the ops team would only update the PaaS when all app owners agree. I predicted that as the certain death of our platform, since it’d take only one laggard app team to render your platform outdated and ultimately obsolete.

It’s good to have some capital stashed away for such moments.

Checking Your Balance

Just like with the piggy bank, there is no easy way to check your balance. The best way to see if you have any credit is to make a small withdrawal. Ask folks for a small favor. If the answer is “we’d love to help, but sadly we have no time”, then you know your balance is near zero.

I follow a pretty strict “no spectators” rule from Burning Man [yes, I did go in 1998, when it was still cool].

I routinely ask folks for small commitments. For example, when someone wants to join my project or meeting, my response is: “Great, we can always use help! There’s this thing we need to get done by next week. Could you take that on?” As you’d expect, I never hear back from many folks.

Genuine favors vs. manipulation

Depositing and withdrawing political capital should not amount to a quid pro quo, where you make a small deposit just to follow with an immediate withdrawal. That will make you appear dishonest. People will assume you use deposits merely as a tool to get your way.

Even if you work to high standards, you are likely to meet people who do this. They tend to bend over to do you small favors that don’t cost them much, like “I’ll walk you to the elevator” or “I’ll pay for this lunch” (likely they have an expense account). There is no surefire algorithm to tell this from being genuine, so you need to find your own comfort zone. I tend to evaluate whether folks wanting to do me favors have something much bigger to gain from my trust and goodwill, e.g. if they are selling into my organization. In these cases, I tend to politely decline any favors.

When accepting favors, don’t be paranoid, but trust your spider sense. If it tingles, don’t feel obliged to accept favors out of social pressure–politely decline.

Similarly, keeping a balance of political capital may make you feel that the main motivation for doing good things is being able to get away with pushing undesirable things. That’s not the purpose of the model. Rather, it’s meant to maximize your effectiveness in bringing (useful) change into an organization.

Cultural differences

How to build political capital and how quickly it gets spent will vary by region and work culture. After all, you are dealing with people, and people’s behavior is subject to social norms that they grew up with. For example, owning your mistakes will be much harder in South or South-East Asia, where harmony and “saving face” prevails. Conversely, folks in Western Europe may blush or grow suspicious if you praise too much. In some places, you may be able to build up a lot of capital without delivering, whereas in others they will heavily discount anything you say until you make it happen.

Perhaps the most widely read book on building up political capital is Dale Carnegie’s How to Make Friends and Influence People with 30 million copies sold (that’s a handful more than The Architect Elevator). While looking at the original table of contents may convince you that Carnegie invented click bait (“do this one thing”), he also cites admitting your mistakes as a technique to form a relationship. To many readers, the book will appear manipulative, most pointedly summarized in an early critique: “smile and bob and pretend to be interested in other people’s hobbies precisely so that you may screw things out of them.” You’ll have to make up your own mind.

Your line of credit isn’t unlimited

Sometimes you run out of capital despite careful planning. A change you pushed for may “blow up”; folks may form an alliance against you; or they may complain about you behind your back and try to undermine your integrity and reputation (all this happens routinely in real politics).

A good manager will generally try to bail you out. I had one manager who fielded a complaint about me being overly protective of my team with “isn’t that a trait of a good manager?”. However, be careful not to become a nuisance. You can ask for forgiveness every once in a while, but if it becomes a regular occurrence, you lose credibility. Your manager may assume you just don’t care about the rules and grows tired of spending their capital to bail you out.

Assume everyone has limited political capital and is spending it wisely.

As junior or mid-level employees we often have the illusion that upper management holds unlimited power. Nothing could be further from the truth. Organizations are (often by law) based on a division of power. Always assume that your superiors have limited capital to spend and allocate it wisely for the political battles that they are fighting.

For any major issue that I identify in an organization, I ask the client executive about their appetite, meaning whether they are willing to spend political capital on it. If we don’t act, it may look like we aren’t aware of or care to address certain problems. But in reality, we just manage our balance and are saving up capital for bigger moves.

Burners

Some people may have appear to have an unusually large stash of political capital to burn through. They may be driving unpopular changes, such as reorganizations or layoffs, or do the “dirty work” for management. In reality, they may have just been hired to spend all their available capital, so their executive sponsors don’t have to dip into theirs.

Transition Executives on a time contract are often brought in for this purpose with the intention to be replaced after they are “depleted”, similar to a burner phone. Top executives may also rotate after a few years for similar reasons and fetch a nice exit package in return for the capital they spent.

Pooling

If people’s individual capital isn’t sufficient for a major withdrawal, they may also pool their political capital with others, knowing that “strength is in numbers”. This can happen top change drivers who spent too much capital by making enemies in multiple departments. Those department heads now gang up to spread negative views or concerns regarding the change driver to make them go bankrupt and have to leave the organization. If that change driver was hired as a burner, they may belief that their method was successful when in reality their move was already anticipated and worked into the change agent’s compensation package. Indeed, corporate politics do resemble a game of chess.

Beware of fair weather friends

As with most people issues, things aren’t always what they seem. Teams supporting you may lead you to believe that you have political capital with them. However, they may simply pursue similar goals, so your work is helping them. But there is no basis of trust and no political capital.

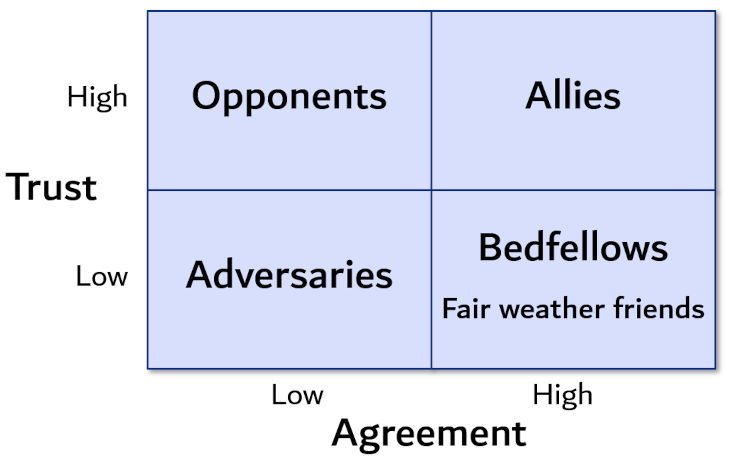

As so often, a 2x2 matrix can expand the solution space and sharpen your thinking.

In this case the matrix is over 30 years old and inspired by the book The Empowered Manager by Peter Block. It makes it very clear that people agreeing with you aren’t always your friends. They might be fair weather friends or bedfellows, who go along for the ride while it’s convenient, but where you have no basis of trust and no political capital.

A model helps you make a decision; it doesn’t make it for you

How and when you use your political capital may vary. The rules for a “burner” may be very different from a full-time employee looking for a lasting career.

The model of political capital doesn’t tell you what to do–bringing change into an organization does’t follow a cookbook recipe. But the model gives you the clarity to better weigh your options and trade-offs. And that likely leads to better decisions, whether for your architecture or your change agenda.

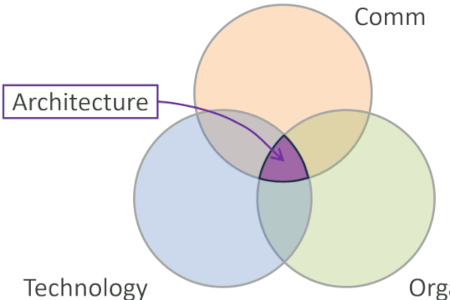

Grow Your Impact as an Architect

The Software Architect Elevator helps architects and IT professionals to take their role to the next level. By sharing the real-life journey of a chief architect, it shows how to influence organizations at the intersection of business and technology. Buy it on Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon Europe