Updated: Category: Transformation

The US automotive industry underwent a transformation in the early 1970s. The oil crisis of 1973 shook the belief of unlimited resources. The novel notion of fuel economy, combined with environmental regulations, spelled the end of the glorious muscle cars from the late 60ies and early 70ies that considered engines with 350 cubic inches (5.7 liters) displacement a “small block”, with “real men” supposedly driving a 454 or at least a 427.

Manufacturers set out to build smaller, more economical cars with smaller engines. However, all they knew was how to build large cars. This transformation literally led to some Gremlins. So, yes, it’s time for another car metaphor. And anyone who expected the title to refer to management consultants offering transformation advice, shame to who evil thinks (or perhaps, wait for a future post). This post originated from a fun conversation with Rod Johnson, after we concluded that car metaphors are awesome, and that organizations routinely screw up transformations.

Compact Cars

How do you make a compact car if you have never built one? Well, you take an existing car and make it more compact, right? That’s what AMC (American Motors Corporation, which rolled up into Jeep, then Chrysler, then Stellantis) did. The story goes as follows:

On an airline flight, Teague’s solution, which he said he sketched on an air sickness bag, was to truncate the tail of a Javelin.

The result was the famously laughable GMC Gremlin, whose design might have had some customers reaching for said air sickness back. The air sickness sketch explains why the hood of the Gremlin spans almost half the car and can house a not-so-compact 304 (5 liter V8) engine.

Funnily, the Gremlin, while having awkwardness written in big letters across its front, did rather well with 671,475 sold in the US and has gained a strong cult following over the years. And it didn’t blow up on rear-end collisions like its Ford cousin, the Pinto, and it appeared more reliable than GM’s PR disaster, the Chevy Vega.

Compact cars aren’t just smaller cars

What the manufacturers ignored, is that a compact car isn’t a big car that’s shrunk down a bit. Compact cars like the Beetle or the VW Golf that arrived in 1974 (both among the longest running and best-selling car models of all time) show that making a car compact requires rethinking existing assumptions–much like any type of transformation. Most compact cars use front-wheel drive and transverse engines, which saves space under the hood and the interior, as no driveshaft tunnel is needed (the Beetle famously used a flat rear engine, which is even more compact, a design that famously lives on in modern 911 Porsches). Manual gear boxes save space and weight, as do independent suspensions. Folding read seats allow for a smaller trunk (boot) that can be extended when needed.

Of course, designing an entirely new type of car requires time, effort, and new expertise, much like a cloud transformation. But there are no shortcuts here, as I mused some time ago in an executive keynote on transformation:

Disruption happens when someone changes the rules of the game. If you play by the old rules, you have already lost.

I see many organizations trying to take shortcuts, figuratively chopping the tail off their Javelins and later wondering why cloud bliss hasn’t materialized. You can also observe many vendors struggling to adapt to shifting market needs, some 20 years after Christensen penned the Innovator’s Dilemma.

But before we get back to IT, let’s fast-forward the compact car metaphor a bit. Real compact gave birth to the hot hatch segment, which served as the base for many famous rally cars. From the early days of the Golf GTI, the Escort RS, and the Lancia Delta Integrale in the 80s and early 90s, this segment has held up for three decades with Toyota’s GR Yaris being the ultimate hot hatch car that should not really be built in 2025: combustion engine, massively turbocharged, thirsty, but oh so much fun to drive (ask me how I know). Perhaps the Gremlin with the 304 engine was the original hot hatch, which would earn it a prominent place in automotive history.

Microsoft Office

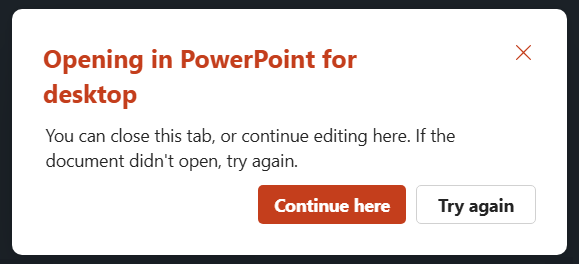

A great Gremlin example is Microsoft Office 365, or at least the variant of it that you’ll see in many IT departments, which are a Frankenstein of cloud, Sharepoint, and desktop application. When someone sends me a link to a file, it opens in a browser. I can’t help but feel flashbacks into the days of VBX controls, but the bigger problem is sluggishness (running a browser-based document editor in a virtual Citrix client is beyond Gremlin, but a frequent reality in corporate IT). So, you click the dots on the top right, select “Open locally”, and are presented with a choice that really isn’t one:

So, apparently I can close this tab or not. Who would have thought? Or I can try again if things went wrong, which appears to be rather likely. But in reality, I don’t want either–I want to work in the local file that I opened.

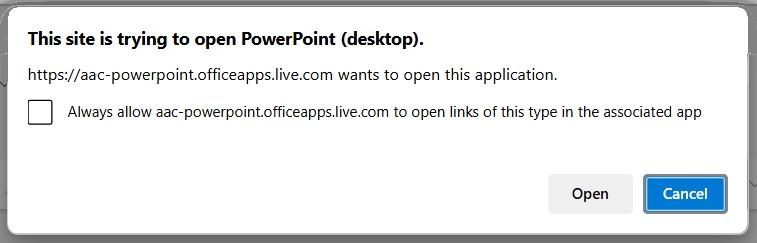

Once you take this hurdle, you are asked to confirm that you indeed want to open the file in the application, because, the previous dialog might have raised some doubts about your actions :

And finally, you are warned that files may contain viruses, even those that come from you. Finally, you can edit locally. But I am told that you have to leave the browser window open for updates to sync back (I don’t really know, but was too exhausted to try it out).

Compare this to Google Workspaces, which never had the desktop legacy. It’s always in sync, it works offline but in a browser, nothing is installed locally, and there isn’t even really a notion of “local”. If I compare these tools and their respective experiences to the AMC Gremlin and the VW Golf, you can easily figure out which one maps to which car.

Choppy tools aren’t just a nuisance; they also affect the way we work. At Google, we would type meeting notes live, with everyone being able to chime in, perhaps fixing typos or adding detail. I once suggested that at Amazon (which struggles with productivity tools because the only viable tools are made by their cloud arch enemies) and got a blank stare: no, we send minutes after we edit them and they are ready for distribution. And if we all edit in Quip (a tool that you most likely will never hear about, and that’s a good thing ), it won’t work. Welcome to Day 2, justified by poor tooling.

Enterprise Non-Cloud

While it’s easy to point at vendors, the same story plays out inside large organizations: of course, we are in the cloud! All we had to do is chop off the tail of our Javelin / change our deployment target. And while we were at it, we kept the big engine bay, longitudinally-mounted engine, and all the rest like our manual change processes and restrictive processes.

Organizations that don’t revisit their basic assumptions will end up with a Cloud Gremlin, or an “Enterprise Non-Cloud”, which I describe in my book Cloud Strategy. Sadly, even 5 years after that book was published, the problem is alive and well in many major IT organizations. These organizations equate manual steps with control and see automation with suspicion, something I tackle with the following observation:

- So, you write a change on a piece of paper, then approve that paper, then have someone log into some machine and type some commands, which should resemble the paper. And you call that control? Come again?

And if they need a cultural reference: (for an admittedly loose definition of culture)

- Automation doesn’t mean losing control. We don’t live in a Terminator movie.

Changing such mentalities is hard, especially as many operations people also equate automation with loss of job. The irony of IT having eliminated many other jobs aside, the main driver of automation is speed and repeatability, not reduction of labor force. But to see that, you need to think beyond chopping the trunk off.

Electric Vehicle Gremlins

How difficult it can be to shed old assumption–the mental legacy–became apparent in a recent LinkedIn conversation. An old friend proudly showed his new electric vehicle built in Ingolstadt. It’s an awesome car, but what immediately struck me is the fake radiator grill (it’s a crossover, so it has a tall hood).

Combustion engine cars have radiator grilles because their engines that rely on a thermal cycle dissipate a lot of heat that must go somewhere (the Beetle was oil cooled–Porsche was an absolute genius). Electric cars don’t have radiators, as easily seen from the Tesla’s closed front. But so many car manufacturers have branded themselves by the shape of their radiator grille: the Bugatti horseshoe, Aston Martin’s wide grille with rounded edges, BMW’s “kidney”.

They now have a difficult time shedding that design element that has been so tightly linked to their brand identity for almost a century.

Most Chinese EVs don’t have such baggage, and I for example find the slightly retro front-end of the Ora Good Cat quite pleasing. Chinese manufacturers have also realized that major technology shifts (like from ICE to EV) level the playing field, wiping out much of the experience that incumbents painfully accumulated over decades. Because the start fresh, they are less likely to produce gremlins. Game on!

Grow Your Impact as an Architect

The Software Architect Elevator helps architects and IT professionals to take their role to the next level. By sharing the real-life journey of a chief architect, it shows how to influence organizations at the intersection of business and technology. Buy it on Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon Europe