Updated: Category: Transformation

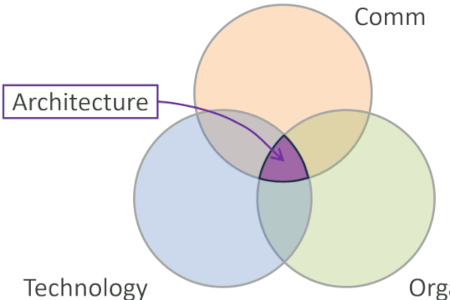

The majority of the software delivery organizations that I work with have no difficulties articulating their goals: they want to use a microservices architecture, become more agile, deliver features faster, have more reliable operations, and, of course, reduce cost. Having well-defined goals is a useful start, but my Strategy books remind us that only a strategy can make these wishes come true:

Strategy is the difference between making a wish and making it come true.

And that’s where a lot of organizations struggle. Their ambitions remain quite literally wishful thinking, despite structured transformation programs that consume investments the size of a small country’s GDP: they keep deploying a giant monolith every full moon, work off a rigid backlog that makes the Niagara Falls look agile, and spend more time in meetings about autonomy than exercising it.

They end up being stuck in old patterns because they haven’t identified the root cause of the behavior they like to change. I cynically describe these organizations as follows:

We renamed everything three times, yet nothing improved.

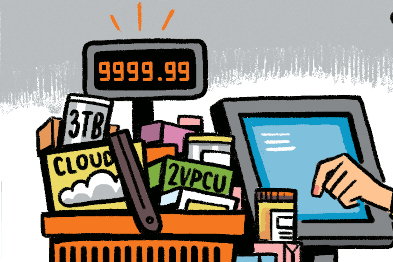

Project teams have become tribes and squads, infrastructure services are now a platform, operations refers to itself as SRE, and the boring old status meeting is known as sprint planning. Yet, unsurprisingly, decision making is as slow as ever, software gets tossed over the wall to SRE, and the long backlog never seems to get any shorter. Worse yet, such reforming-by-renaming activities rob words of their intended meaning. In an environment where the installation of a tracing tool is hailed as observability, a cloud spend report is euphemistically labeled FinOps and every team is a platform, how do you actually drive observability, FinOps, or a platform strategy?

Such a frustrating situation has been aptly described in the Matrix movies:

You hear that, Mr. Anderson? That is the sound of inevitability.

Expecting changes in behavior without changing the mechanisms that caused the behavior in the first place is an illusion that rivals the Matrix itself. Dan North once described it with a car metaphor, hitting my well-known soft spot:

If you want to reduce emissions on your car, you need to tune the engine, not plug the exhaust.

Without understanding the root cause for big releases, too many meetings, or long requirements lists, you cannot simply wish them away. You have to go to the engine and tune it–or replace it with an electric motor. That’s more effort than plugging the exhaust or putting up motivational posters. But in contrast, it carries at least a chance of success.

Understanding cause and effect

Two main elements inhibit any change in the way of working:

1) People’s experiences shape their behaviors, reinforced by mental models and assumptions inside their heads.

2) The system that people work in exhibits constraints, which shape or reinforce these assumptions and mental models.

A canonical example can be seen in a very common IT ailment: endless requirement lists proudly handed by the business to IT. It’s so common that I coined a cynical slogan for it:

Business got used to IT delivering half the stated requirements, so by asking for twice as much, business hopes that it may get the right half.

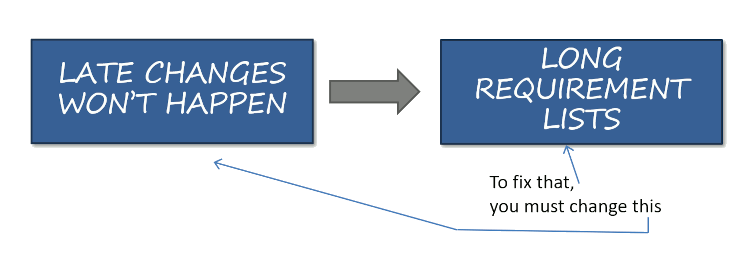

IT keeps pushing the business to prioritize their needs–with little effect. That’s because it’s not hitting the root cause: the business has learned over time that anything not on the initial requirements list is eternally “out of scope” due to budget constraints, outsourcing contracts, or timeline commitments. That means late changes can only be delivered with a pricey change order, or more likely, never. Once the root cause is clear, the answer becomes apparent:

To shorten requirements lists, you need to prove that you can accommodate late changes.

So, rather than sticking an “agile” label on your projects, you need to understand the core mechanisms behind agility: regular re-prioritization. One of my favorite quotes from Mary Poppendieck aptly describes that way of working: “A late change in requirements is a competitive advantage.” Following that single sentence does more than renaming all existing project managers to product owners or SCRUM masters.

Identifying Root Causes: Adding an index to your brain

My Architect Elevator workshops teach architects how to reach the upper floors of an organization and how to drive change. That’s why we brainstorm the root causes of common IT ailments, such as large projects or big, finicky releases. When I pose the exercise, participants often look puzzled because they aren’t used to making the connections between cause and effect, which often appear distant. But since they live through them every day, they invariably produce extensive lists of real-life examples.

This makes this exercise particularly rewarding for me, as attendees uncover knowledge that they possess, but were unaware of. Given the technical audience, I describe the effect to them as follows:

You have the data, but it’s not indexed. So, accessing it will take some time and effort.

It’s a great way of making others smarter, one of the key things we like to do as architects.

Common Root Causes and Effects

I share a few examples that were generated by collective human intelligence, not LLMs, which would confidently generate a long list of plausible but meaningless reasons. I anticipate that you have observed some of these effects on your projects:

Friction leads to larger pieces

Ever wonder why projects are so enormous, releases are infrequent, and teams are big? The culprit isn’t people slacking off: it’s excessive friction. Friction comes in many forms and shapes: if the overhead of creating a project is high (think business case, project plans, security reviews, steering committees), then large projects appear more efficient. Likewise, manual release processes that are error-prone and labor-intensive, lead to less frequent, larger releases.

We know the same effect from the non-IT world: the music album, which bundles many songs, is the product of the high manufacturing and distribution cost of physical media, a form of friction. Stamping, shipping, and stocking a single song on vinyl or CD is in most cases too expensive (some day I’ll dig out my cherished maxi singles, which are a notable exception). With streaming, the friction is gone, and the notion of releasing an album has essentially lost its meaning.

If you want smaller pieces like microservices or frequent releases, you have no choice but to reduce friction. Everything else is window dressing, or plugging the exhaust pipe, for those who share my love for car metaphors.

Long lead times lead to hoarding

In on-premises environments, getting a server or a database instance can be arduous, and time consuming. But the reality is that many teams have a spare server stashed away somewhere. So, if you’re plugged into the black market, you can get a server quickly.

We’ve seen the same effect during the pandemic when tissue paper ran out everywhere–I believe my dad still has some in the basement. When procuring resources has a long lead time, and they are hard to come by, people start hoarding. It’s a natural reaction, because you never know when you can get more, so you better grab extra when you can. Ironically, hoarding exacerbates the supply-chain shortage, as anyone who has played the beer game has experienced.

If you want to meet your scaling needs in the face of long lead times or arduous procurement processes, you keep a server or two on hand. To remove this hoarding and the black market, organizations sometimes review inventory or send detectives to uncover unused server instances. Rarely does this yield much–black markets are hard to penetrate. Instead, you must identify and remove the root cause: make resources easily available through self service and elastic infrastructure. Allocate server cost to the projects to avoid the Tragedy of the Commons. Such “democratization”, as cloud providers routinely call it, will make the black market unnecessary and unattractive. Once the root cause is identified, the solution becomes apparent.

High utilization leads to low throughput

This effect is well known in the context of lean manufacturing: high utilization optimizes resource usage, but leads to long wait times and low throughput. In organizations where everyone’s calendars are full, getting a simple meeting may take weeks or even months of elapsed time for 45 or 60 minutes of productive time. And, yet again, intuitively people make the problem worse: they add lockers to everyone’s calendars, which makes it even harder to schedule any meeting.

Fixing the cause is counter-intuitive: reducing utilization. You’ll worry that you will get less work done, but in reality, you’re reducing activity, not progress. In many countries, this insight is used when heavy traffic causes speed limits to be lowered, which in turn increases the throughput (at the expense of optimal latency).

Low trust leads to low reuse

Virtually every IT environment wishes for more reuse. However, in those same environments, teams are pitched against each other, for example by individual KPIs, which leads to competition and low trust between teams. This, in turn, hinders reuse: teams prefer not to depend on other teams’ work because it can present a leverage point for the other team and a risk for them. I have seen teams weaponize Github access, a service that they controlled.

Also, teams hesitate to share their work for fear of being blamed for other teams’ issues. When I worked in an environment like this any opportunity for reuse was countered with “who pays for the usage of my service?” Establishing a common platform in such an environment is very challenging, as each team prefers to build their own services. You won’t success unless you can establish trust.

Lack of data leads to a lying contest

Most IT projects are funded based on value projections, which are (hopefully) realized after project delivery. That point in time can be 18-24 months out, though. Because there’s little data to support these projections, they really are promises. Will that $10 mio project really generate $20 mio in benefits for the next three years after delivery? We hope so, and the spreadsheet says so, but only reality can tell.

Teams and steering committees rarely go back and check whether projected benefits materialize. There’s little to be gained from doing so, as the $10mio won’t be coming back, anyway. Predictably, this lack of feedback favors ever more optimistic promises, which will ultimately trigger a lying contest where ever bigger promises that are less likely to come true. If your project promised $20 mio in benefits, mine will at least make 22, or so my spreadsheet says.

Naturally, this isn’t a great way to run an efficient IT organization. But the only cure is to make decisions based on hard data, not promises. Where can you get data about the future? Experiments, early releases, test runs, MVPs. The vehicles are widely known, just rarely implemented because it’s oh-so-inconvenient when reality doesn’t agree with your projections.

Effect and Cause: Positive feedback cycles don’t have positive outcomes

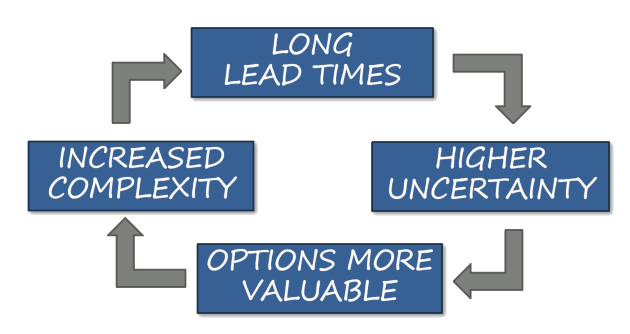

Sometimes the effect itself is a cause, in which case things get even worse. In systems theory, this is called a positive feedback loop. However, the result is nothing positive. A good reminder is that an explosion is also a positive feedback loop: more heat releases more oxygen, which fuels the fire, which generates more heat.

In IT, the explosion unravels more slowly, but the results are equally devastating. A canonical example relates to the notion of architecture options: an organization that has long delivery timelines (24 months is not uncommon) faces high levels of uncertainty–a lot of things can change over the course of 2 years. So, they want more options: make it scalable, portable, extensible. Now they face Gregor’s Law : if you want all the options, you’ll drown in complexity. And guess what, complexity slows you down. You have now come full circle, in a bad way!

Now that effect is also a cause, you may wonder where to start breaking this cycle. In this example, the natural starting point are the lead times: you’ll have to break large deliverables down into smaller, incremental ones, which carry less uncertainty.

Don’t be a fatalist

Not seeing the root cause of common IT ailments leads to unfulfilled wishes, empty promises, and desperation (a bit like fear leads to anger and anger leads to suffering). Running an exercise of brainstorming root causes can open team’s eyes to the hidden dependencies. It’ll seem awkward at first, but you’ll be amazed by the insights you gather. After all, architects see more than other folks.

Grow Your Impact as an Architect

The Software Architect Elevator helps architects and IT professionals to take their role to the next level. By sharing the real-life journey of a chief architect, it shows how to influence organizations at the intersection of business and technology. Buy it on Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon Europe