Updated: Category: Transformation

Many customers appreciate case studies that show successful implementations of a vendor’s technology. Not surprisingly, developing referenceable customers ranging from sports leagues and major events to large enterprises, start-ups, and communities are part of most any sales playbook.

Although it’s great to see the positive impact your technology has had on such a wide range of customers, I can’t help but feel reminded of the before-and-after photos in weight-loss ads: look, this person has had amazing results! But will you?

My impression might stem from success stories focusing on the initial state and the end result, leaving the steps in between somewhat fuzzy. Worse yet, those depictions can lead you to believe that the organization made one giant leap: from traditional-slow-inefficient-intransparent to cloud-native-automated-agile-digital in 20 days!

The reality is that such success stories rarely, if ever, occur as one giant leap. I often remind customers looking to transform:

If your organization is a bit behind others in terms of operating model, the chances that you’ll be able to make a giant leap ahead are very slim.

Instead, you should consider going in circles.

Going in Circles Isn’t All Bad

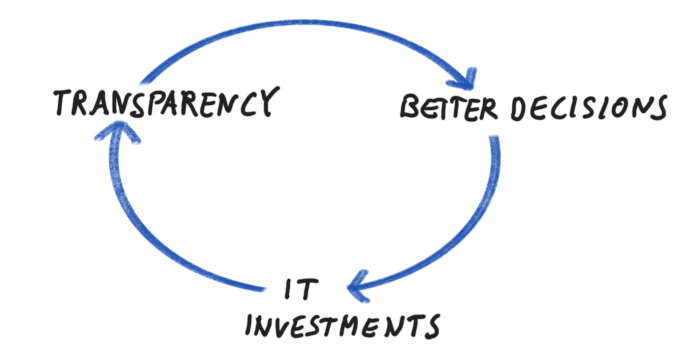

My recent post on the AWS Enterprise Strategy Blog describes the cloud transformation value gap—value creation slowing down when cultural change doesn’t keep pace with technical progress. To get over this hurdle, the post recommends several strategies, one of them being a cycle like this one:

This diagram shows a virtuous cycle:

- Better transparency into you IT systems, perhaps through better metrics, benefits decision-making.

- You can now make better decisions to invest where you realize the most value, improving the ROI for IT investments.

- These investments in turn increase transparency, for example by breaking software monoliths down into microservices or increasing infrastructure automation.

- This transparency enables even better decisions as you now have finer granularity and higher accuracy of data.

This loop increase values by repeatedly and reciprocally improving both the organizational capabilities (decision making) and technical capabilities (such as automation). Each cycle might only be a small improvement: a refactored component, improved monitoring, or a CI/CD pipeline.

Positive Feedback Loops

Such loops are known as positive feedback loops (Wikipedia): one element in the loop feeds another, which in turn boosts the original element. Positive feedback loops are well-known in real-life. They are sometimes called “explosive” because they feed on each other just like gun powder or other explosives: gun powder contains a strong oxidizer that releases oxygen when heated; the oxygen fuels the fire, which leads to more heat. The result is a rapid combustion.

Peaceful examples include the decline of public transportation due to decreased ridership, leading to schedule reductions, which in turn discourage more people from using public transit. Likewise, poor economic conditions lead to reduced spending, which in turn slows the economy. The word “positive” in these feedback cycles doesn’t imply that the results are beneficial—it merely denotes that the feedback further adds to the effect.

“Positive” in the context of feedback loops denotes the type of feedback, not a good outcome.

Of course, positive, positive feedback loops also exist: more participants on a social network attract more new participants; more users of new technology reduce the cost of equipment, leading to broader adoption; a population becoming more health-conscious leads to more restaurants serving healthy food, which entices more people to follow the trend. Positive feedback loops are virtually everywhere and are often cited as a key element of the platform economy.

Transform by Going in Circles

If you’re trying to bring change into an organization, feedback loops can be extremely helpful: they allow you to start small and ratchet your way up to continuous improvement.

Each cycle in a feedback loop enables another one that might not have been possible or economical before.

The important aspect is that each cycle in the feedback loop enables another cycle that might not have been possible or economical before. For example, improving your software delivery reduces the cost of building software. More economical application development leads to increased usage of the delivery platform, further improving the platform’s economics and allowing the addition of more features. Thus, the fruitful cycle continues.

Predicting Cycles Is Hard

The main challenge with positive improvement cycles is that their behavior is, like most complex system effects, difficult to predict. While most chemical substances have been tuned for controlled explosions over time, rapid feedback cycles lead to small variations having amplified effects.

That’s where many IT transformations struggle: IT projects are based on defining a specific target picture, calculating the potential benefits, and comparing them against the required investment. This may work for a single “leap” but is extremely difficult to predict for positive feedback cycle that can have many rounds. As a result, the feedback cycle may never get started.

Understanding positive feedback is more than just iterative development. Breaking a large chunk of work into smaller pieces is certainly useful. It mostly assumes, though, that the pieces simply add back up to a whole over time. Positive feedback loops differ in that one new piece makes another one possible, so the end result is more than could have been achieved in one single run.

Iterative development assumes that the incremental pieces simply add back up to a whole. With positive feedback loops, one piece actually makes the next one possible.

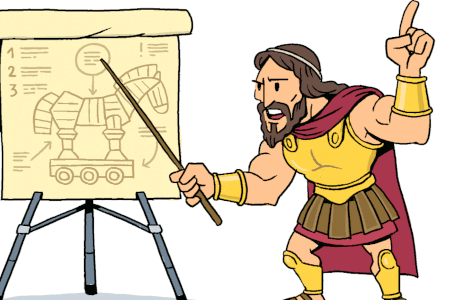

Fake Explosive Charts

Many IT folks have realized that gaining traction for new initiatives is difficult: you need to overcome the chicken-or-egg problem of not having initial demand, which in turn might not justify the investment. It’s like electric cars and the charging stations - hardly anyone wants to buy a car when there are few charging stations around. Alas, building charging stations for cars that haven’t been sold yet is equally poor business.

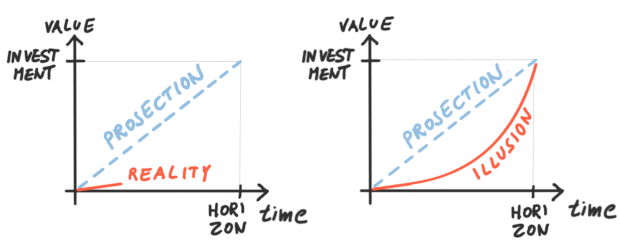

This conundrum makes building a business case to recover the investment over a fixed time horizon difficult. Interestingly, clever IT folks often find a “solution” by drawing an exponential adoption chart for their proposed projects:

Despite a slow start, these curves predict a rapid “explosion” of demand just in time to satisfy the business case over the pre-determined horizon. Such curves are usually reverse-engineered from the required return and time horizon—I believe Excel has a function for that. Sadly, such curves have little to do with positive feedback cycles. Without detailing what feeds the loop, they are just a pseudo-scientific form of “all will be good” hand wavery. By the time reality hits, the project will be well underway and is unlikely to be stopped. As architects, it’s our job to recognize such scams.

Just drawing some sort of exponential curve doesn’t imply the presence of a positive feedback cycle. It might be an illusion.

Detecting Duds

Positive feedback loops also allow you detect early if your explosion is a dud, i.e. fails to ignite. Of course you can’t expect miracles (those usually work only on PowerPoint slides), but if you find that there’s no adoption for your automation, you are unlikely to gain the additional transparency that feeds the cycle. The good news is that you can stop right there and try to re-kindle the fire before making additional investments.

You Need a Detonator

To squeeze the explosives metaphor one last time, most explosive materials need a detonator, a small explosive device that triggers the main charge. That’s a good thing because it keeps the explosives from going off by themselves, as was repeatedly the case with nitroglycerin. We can also compare it to a starter motor of a combustion engine: to get the engine running, you need a small motor to crank it first. That’s why you’re stuck even if you have a full tank of gas but a flat battery.

The initial investment needed to get the wheel spinning is unlikely to have a positive business case.

IT projects, even those with positive feedback cycles, also won’t just start by themselves. You need to invest first to create the initial movement, i.e. provide the trigger. You need a starter motor and a battery. Keep in mind that this very initial investment is unlikely to have a positive business case. It’s sole purpose is to get the chain reaction started. Applying traditional IT metrics would therefore stall the whole initiative before it even gets going. It’d be like determining that the starter motor isn’t able to move your car. That’s not its purpose.

The Flywheel

If you feel that black powder and nitroglycerin are unusual ways to describe IT projects, allow me to conclude with a more business-oriented example. A core element of Amazon’s business model, and an integral part of its internal culture, is the Amazon Flywheel, reportedly drawn by Jeff Bezos on a napkin.

This positive feedback loop reflects that a better customer experience leads to more traffic, which attracts more sellers, which increase the selection and further improve the customer experience. Amazon’s fly wheel benefits from the second effect that growth improves the cost structure, which allows price reductions that in turn improve the customer experience. This flywheel is a real (and peaceful) example how a positive feedback loop has led to nothing short of explosive growth, without any giant leaps.

Grow Your Impact as an Architect

The Software Architect Elevator helps architects and IT professionals to take their role to the next level. By sharing the real-life journey of a chief architect, it shows how to influence organizations at the intersection of business and technology. Buy it on Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon Europe