Updated: Category: Transformation

Metaphors are more than a figure of speech for architects; they are an essential tool to transport technical concepts into their audience’s world. The Architect Elevator is a metaphor–in reality, the company leadership may be sitting on the same building floor as you; my car metaphors could fill an entire book; and “Architecture is Selling Options” has become the anchor of many architecture keynotes. So, at least my world of architecture is full of metaphors.

Let’s explore what makes metaphors so powerful and how to discover good ones.

From your world to theirs

Architects riding the Elevator translate technical concepts across the layers of the organization. The goal isn’t to make things simple (they generally aren’t), but to help decision makers understand–and agree to– decisions and trade-offs made in the IT engine room. Establishing this link is more important than ever because technical decisions directly impact the business’ ability to innovate and maneuver.

But engineers in the engine room and decision makers in the board room live in different worlds and speak different languages. That’s why you often see presentations with “all green” options, which are purported to be superior in all aspects–usually positioned against contrived “all red” alternatives. Such attempts at showing that “everything will be fine” provide only a weak form of buy-in:

Real buy-in means accepting trade-offs and constraints, not just liking a wish list.

The presenters who show “all is green” options mistake captivating for capturing. They want to lock up the audience’s thinking to get an easy pass. Good architects set the audience free to think for themselves, to understand trade-offs and perhaps identify blind spots.

But conveying trade-offs requires understanding the domain: A microservices architecture can increase system resilience, but requires strong DDD skills, standard APIs, and managed middleware. The inevitably more complex run-time environment also necessitates observability and distributed system design skills. Balancing service granularity and carefully defining aggregate roots can address these considerations. Sounds like a trip to the engine room? Technobabble is the term we use when folks from the engine room bury the audience in terms that mean little to them. It’d be a noble endeavour to explain all these terms, but it’d make for an awfully long “ramp” for the reader (see “Explaining Stuff” in the Architect Elevator)

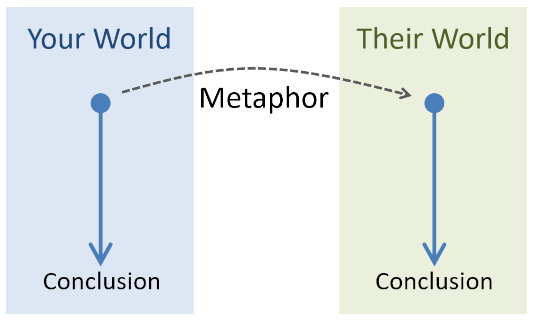

Well-placed metaphors can work miracles (metaphorically speaking) in these situations. Rather than explain the intricate dynamics of your environment, you compare it to an environment that is known to the audience and exhibits similar characteristics.

For example, instead of using a monolithic cargo plane, you can transport goods using smaller drones. The failure of one drone will have less impact, but you need to invest heavily into coordination and organize everything in drone-size packages. Also, you’ll have a lot more air traffic, so your traffic controllers will need better tools.

Metaphors translate your problems into the audience domain, so your audience can reason about it.

Because the metaphor shares the dynamics and constraints of the IT solution, your audience can reason in the metaphor and understand the decisions and trade-offs made in the IT engine room. When your audience picks up your metaphor and begins to explore, for example to validate their understanding, you know that your translation worked. This is also how you know that the analogy goes beyond a glorified example or cute illustration.

Racing past the finish line

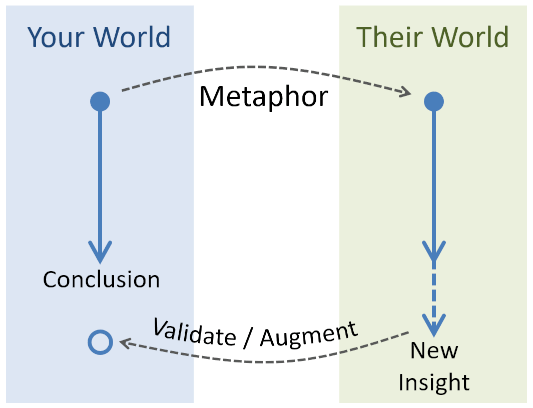

The real magic happens when your audience takes the metaphor further than you have envisioned. The metaphor then becomes a tool to amplify and sharpen mutual understanding, which are hands down the most valuable session I have had with executives.

You can now learn from your audience because you have given them a domain that they can reason in. In such a situation, everyone wins as you have progressed from explaining to co-thinking. Because this mode is so valuable, my advice is:

If the audience embraces your metaphor, forget all the other slides and run with it!

Your remaining “explaining” slides are less valuable than having your audience explore the solution space and trade-offs based on your metaphor.

Some Mighty Metaphors

Several of the metaphors I use have allowed the audience to run past the finish line and sharpen my own understanding in the process. It won’t happen every time, but good metaphors give your luck more chances.

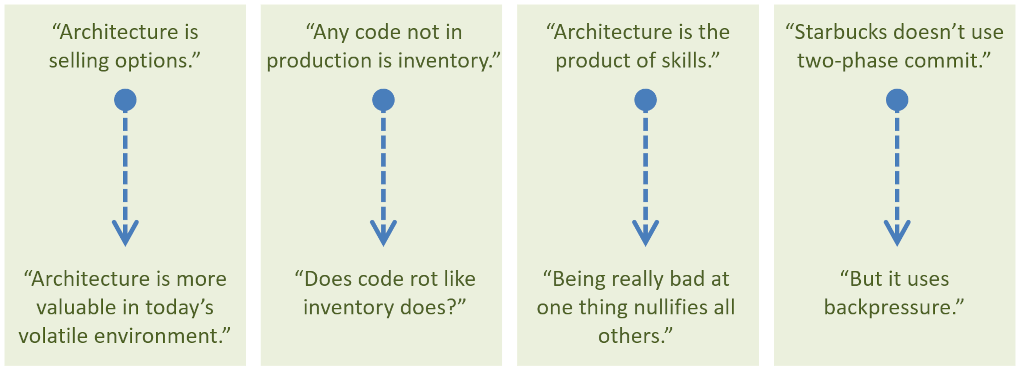

Options become more valuable in face of volatility

One of my best-known metaphors is that architects sell options. The metaphor highlights that the key contribution of architecture isn’t to make decisions, but to postpone them, just like financial (or real) options do. Black and Scholes calculated the value of options, which makes a nice way to prove the value of architecture.

When I shared this metaphor with a senior executive at Allianz, he quickly observed that volatility drives up the value of an option (captured in the formula as sigma), leading him to conclude that architecture is more valuable in our volatile times.

Software inventory rots

During my Architect Elevator Workshops, we practice selling speed (or velocity) to a CFO who only cares about cost. I won’t give away the entire story here, but one key translation vehicle is that of inventory. All unreleased code is inventory, and any financial executive understands that inventory carries a cost without any revenue standing against it.

When you share this metaphor with a financial executive, they may quickly recall that inventory doesn’t just carry a cost, it also loses value: inventory rots, whether it’s cars on the lot that will be worth less by the end of the model year or milk on the grocery store shelf that becomes a liability in a matter of days. Your counterpart may therefore ask whether software inventory also loses value. To which you should answer with a resounding “yes! we call that ‘code rot’”. Then you can go on to explain that long-lived branches will be harder to integrate (a cost), or it takes longer for developers to pick them up (also a cost).

A zero skill cancels out all others

I recently published a blog post stating that becoming a great architect isn’t about adding more skills, but about becoming a force multiplier. When I shared this post on LinkedIn, a reader quickly picked up the metaphor and pointed out that in multiplication one factor of zero nulls out the product. They then translated this back to architecture skills, deriving that if you are horrible at one skill (earning a zero), you can’t make up for it by boosting the other skills. Put in a punchy way:

If you know everything but no one wants to talk to you, you provide zero value.

The point is less about whether I agree with the reader (I mostly do), but that the metaphor encourages people to think further based on the metaphor.

Starbucks uses backpressure but McDonald’s doesn’t

My blog post on why Starbucks doesn’t use two-phase commit is still one of my most widely read articles (it’s also a chapter in The Software Architect Elevator and Best Software Writing). A reader who used to work at Starbucks built on this metaphor by stating that under extremely high load (and all baristas running at max capacity), Starbucks will use backpressure: the order takers slow down to shift the traffic from the pickup area to the order queue, which scales more easily.

A friend took this yet one step further by voicing his frustration that McDonald’s fancy ordering system does not, meaning that the fully digital ordering experience was followed by an excessive wait time for his meal.

In all cases, the metaphor led to stronger audience engagement and deeper understanding on both sides:

Finding suitable metaphors

Folks invariably ask me how I come up with these metaphors. Although I don’t have a reproducible recipe, I can share some tips about where to find sticky metaphors:

Money

Most any executive know how to manage money. That’s why translating architecture decisions back to options, net present value, internal rates of return, volatility, etc. works well. Money also has the advantage that it’s been around for some time and has a solid theory behind it, like the Black Scholes equation referenced above.

The Primary Business Domain

Metaphors from the main line of business work equally well. Retailers or manufacturers can relate well to supply chains, software provenance, inventory, distribution, just-in-time, or the cost of delay. Translating your technical decisions and trade-offs into the business domain also shows your audience that you have an interest in the business side of things. I just advise that making too specific references can stir business debates that distract from your architecture message. So, comparing software delivery to a supply chain probably works well, but folding in an ailing vendor or belaboring a real inventory issue may stir up too many emotions.

Widely Used Items

I am somewhat famous for car metaphors. Cars are rather complex machines that most any person uses or at least knows about. Housing would be another candidate, but then you run into the danger of comparing IT architecture to building architecture, which is a well-known slippery slope (ah, these metaphors!). Car metaphors are fun, but they also carry a certain gender bias, as do many sports metaphors. So, try to be inclusive.

Generally, it’s helpful to stay with one metaphor or one domain throughout your session. Jumping between financial options, gardens, cars, supply chains, and cooking can perhaps be pulled off in a high-powered keynote, but is likely to overload an executive conversation.

Words of Caution

Not all metaphors work well. Listeners who aren’t familiar with the metaphor may be more confused. Similarly, overusing metaphors–especially sports metaphors–can annoy some audiences. Not everyone is keen to touch base to tee off an initiative so that we won’t drop the ball just before the finish line. Here are some traps to watch out for:

Frivolous imagery

A good metaphor isn’t just a catchy image–it needs to hold up to the logic. Otherwise it’s not a thinking tool, but merely decoration. That’s not much better than those “motivational” images of people rejoicing on top of a mountain summit facing an over-saturated sunset.

When recording a series of videos on organizational transformation, we used a wide range of props. Initially, these were either determined by the filming location, like a pool table that couldn’t be moved, or chosen by the video crew to make the video less boring. However, many of them appeared ancillary or even frivolous, as they didn’t relate to the script. It seemed like you’re listening to one thing (IT transformation) while you’re watching another thing (me making tea or salad).

Good metaphors aren’t a side channel, they make a connection. So, I decided to rewrite the script to integrate the props directly into the storyline. This resulted in layering being explained with Jenga or agility being demonstrated by a scooter needing to avoid a plastic horse. It took quite a bit of extra effort–and the willingness to make late changes. But to me it was entirely worth it: the connection between props and core message made the story more engaging and amplified the messages.

Broken metaphors

As you’d imagine, not all my metaphors came out right the first time and may need refinement or replacement.

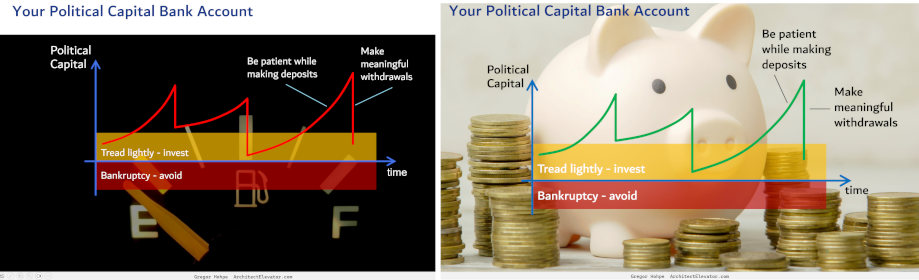

In my Architect Elevator workshops, participants brainstorm based on the metaphor of political capital, which indicates the level of the trust and goodwill you enjoy in the organization. My weakness for car metaphors quickly led me to use a gas gauge as a visual metaphor for the amount of capital you have. An astute workshop attendee pointed out a fundamental flaw in this metaphor: the behavior of a gas tank is the inverse of political capital. The former fills fast and drains slowly, whereas the latter fills slowly and depletes quickly.

Based on the feedback, I changed the metaphor to that of a piggy bank, which also fills up slowly but empties fast. It also relates to money (capital), and you can’t see how much you have until you crack it, much like political capital. Share your metaphors and be open to feedback!

Slanted metaphors

A metaphor may carry a bias or steer your audience to one direction or another. If you compare Kubernetes to a Rube Goldberg machine, it’s predictable that executives see it as a complicated but not-very-useful toy. You may consider this accurate, but if you are aiming for a balanced discussion, this isn’t the metaphor you should choose.

A good metaphor should have tension by showing advantages and disadvantages. When likening transformation agents to the clutch of a car, the metaphor highlights the benefits of decoupling speeds, but it also reminds folks that a grinding clutch takes all the heat.

You may not end up with perfectly neutral metaphors all the time, but they should pass the “mirror test”: look at yourself in the mirror and check whether you fully stand behind the metaphor.

Risky business

Just like in any good party conversation, you should stay away from metaphors that relate to religion, race, politics, or similarly sensitive domains. Also, while we may not think much of saying that political references can be a mine field, I try to avoid military metaphors.

A secret method?

Good metaphors rarely arrive at the push of a button, and I don’t have a secret method either. Instead, I give the following advice:

- Be patient: It took me a decade to come up with my collection.

- Don’t lose the good ones: Rather than stressing about finding new metaphors, make sure you don’t lose the good ones you came up with. A lot of my ideas originate from casual conversations, but they are easily lost when you get back to your desk or troubleshoot the next issue. Keep a log!

- Get feedback: Test and refine your metaphors with a friendly audience. Many of my catchy metaphors started with simple sayings and evolved through conversations and feedback.

- Make it your thing: I used to feel a bit embarrassed about using too many car metaphors until I decided to make it my shtick. If you’re upfront about it, your audience will be more forgiving, and people may even want to share new metaphor ideas with you.

- Capture it in a visual: My books are full of metaphors and cartoons, from legacy systems rising in the Night of the Living Dead to a hotel receptionist representing multitenancy. A catchy visual makes your metaphor even more sticky and more fun to reference.

Most of all, be creative and playful, let your mind drift a bit–you may be amazed how many metaphors pop up once you take a step back from the daily grind of corporate IT.

The path to the mountain of gold leads through the swamp

I like stretching metaphors to test their limits. It doesn’t always work, but when it does, it turns the metaphor into a storyline that continues further than the audience expects.

A fun metaphor that I sometimes use to close my talks on transformation plays off the fact that before things get better, they initially get worse. It’s like you’re making your path to a (promised) mountain of gold, but to get there, you first have to cross a swamp.

So far, it’s an OK metaphor, but we can stretch it a good bit further: folks are naturally hesitant to cross the swamp. After all, who wants to get wet feet? So, you remind them that the best time to start moving is today. Why, you wonder? Rising ocean levels: we can wade through the mud today, but tomorrow we’ll be swimming!

The message is serious, but the metaphor delivers it in a playful way. Given how boring most IT presentations are, a bit of play is very welcome in my opinion, especially if it isn’t frivolous, but delivers an important message.

Metaphorize your executive presentations

Metaphors can be a major asset in executive presentations because they pull the audience in. They are catchy and relatable, but also carry a relevant message. As always, consider the appropriate volume level for your audience. If you want an example of “Volume 10”, listen to this part of my favorite talk by the late Russ Ackoff. Now, strangely, his reference makes me remember the horror comedy Idle Hands, which is surely beyond what you’d want to discuss in a board room. Know thy limits.

Grow Your Impact as an Architect

The Software Architect Elevator helps architects and IT professionals to take their role to the next level. By sharing the real-life journey of a chief architect, it shows how to influence organizations at the intersection of business and technology. Buy it on Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon Europe