Are IT's biggest decisions its worst?

Updated: Category: Transformation

Some time ago my friend Woody Zuill explained: “estimates are a way to make decisions; so is this:”, pointing at the coin in his hand that he was about to toss. His pointed example highlighted that the difficult part isn’t making a decision, but making a good decision. Let’s have a closer look at how this works in IT.

IT Decision Making

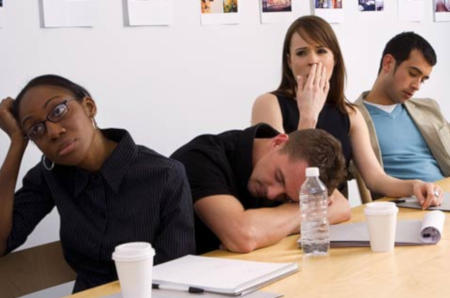

Frequent meetings seems to be an accepted reality in large IT shops: working committees, steering committees, task forces, status updates, jour fixes, planning meetings, and many more. The general idea is that these meetings are there to share information, build consensus, and then make decisions. In reality, we’re lucky if wading through lengthy slide decks can pass as information sharing, applying a generous dosage of goodwill.

In most cases, though, teams presenting in decision or steering meetings aren’t terribly keen to share too much information about what they’re up to. That’s largely because the meeting preparation takes so much effort that the team has already essentially made a decision by the time the options are presented to a larger or more senior audience. Any change in direction at that point would imply major rework, so the general goal is to pass the review without any changes.

The question then is, how useful are such meetings, really? To answer this natural question, we first need to have a closer look at how IT decision-making works.

IT Hierarchy

Like most large organizations, IT is structured in a hierarchy: at the top there’s a CIO or a divisional CEO of the IT department, followed by deputies, heads of departments, deputy heads, area leads, etc. The hierarchy divides teams along two dimensions. The area of responsibility is largely set by a certain functional area, such as infrastructure, application delivery, ERP, etc, while the level in the hierarchy is generally determined by the number of people reporting into the position and the spending authority.

The level in the hierarchy is largely determined by the number of people reporting into the position and the spending power.

This setup is a holdover from the days where IT was largely run as a cost center: headcount expense plus cash spend for hardware, licenses, and services represent the majority of the IT cost - facilities and other items making up the remainder. So, the more money one controls, the higher up in the hierarchy you’d be.

Side note: as an Elevator Architect I make sure to break either tradition by not having any reports, nor any budget authority, and not being constrained to a functional area. I also remind people that a bad architecture decision can easily blow millions of Dollars, regardless of your title.

How big is a decision?

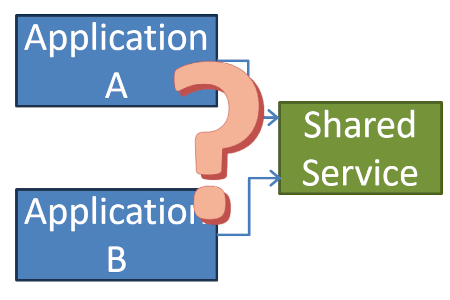

The second factor that influences IT decision making is money: generally lacking strong and broad architectural guidance, much of IT decision making takes place by budget. Initially this make sense because it’s one thing to tank $5,000 on an ill-fated project and another one to have to write off $5,000,000. Therefore an IT decision’s importance is determined by the amount of money to be spent – “bigger”, as in “more expensive”, projects deserve more scrutiny.

Another reason to focus on budget is that approval and procurement are usually some of the more effective governance mechanisms in traditional enterprises. A buy over build approach and large-scale outsourcing has often reduced IT to a mere project and budget administration function. Hence, internal processes follow along this focus on spend control. Lastly, budget approvals don’t require deep domain or technical knowledge, allowing a small team to moderate a broad range of purchases.

Your biggest architectural decisions may involve very little money, at least as measured by existing processes.

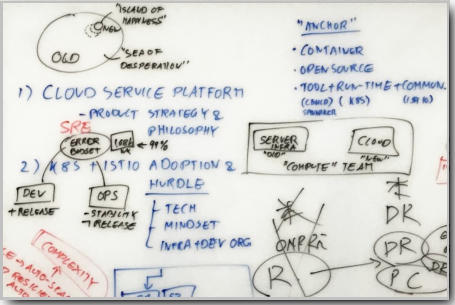

Of course, an architect will see that there’s a lot more behind the importance of an IT decision than money. In the extreme case, critical architectural decisions can involve very little money. For example, you may decide to prefer open source products and open standards wherever possible. Initially, this decision may not appear to cost anything as it’s not tied to any product purchase. More interestingly, some may present this decision as a cost savings measure because open source products are “free”. Once you factor in all ramifications of these decisions, you realize, though, that theres a lot at stake, including money:

- Open source products may lack specific features that could give you a competitive advantage.

- Open source products may require specialized skills sets that are difficult (and therefore expensive) to attract.

- Open source products may require more customization than commercial ones.

- Open protocols may be designed for broader usages than your specific use case and therefore more complex.

- Open protocols may simplify integration with other components or external partners.

- Open source project may give you the flexibility to add features if you have the right skill to do so.

I am sure you can come up with more items to add to this list, underlining the fact this decision is much more wide-reaching than it may seem to the procurement department. As an aside, for a thorough look at lock-in, especially in the context of open source, see my article on Martin Fowler’s site.

Deciding from High up

Judging the size of a decision by the associated spend and running more expensive items up higher in the hierarchy means that big decisions are made “high up”. This makes some sense as decision makers in higher positions often have a broader context of the different initiatives and can thus detect overlap or gaps among the project portfolio.

However, this model has one grave disadvantage: it means that the more significant a decision is, the further it becomes detached from the technical details and reality. That’s because the decision is passed through so many layers of IT management that by the time the decision is up for review, the chances that there’s someone in the room who can actually pose or address detailed technical concerns and considerations is slim to none.

The more relevant a decision is, the further it becomes detached from the technical details and reality.

Would a round of senior IT managers really have a good view on whether wrapping everything in Kubernetes operators is a good idea, whether giving sysadmins an “easy-to-use” GUI is better than command line scripts, whether buzzwords like “GitOps”, “automation”, or “IaC” (Infrastructure as Code) really mean something different, or whether low-code tools are the way out of a skill shortage? Perhaps not.

Failure doesn’t respect organizational layers

In fact, “let’s not go into details” is a common management directive mis-guided by the belief that good managers don’t need to dabble with technical details. That’s left to the programmers or contractors as it may be, because, after all, we manage by objectives and don’t micro-manage. I summarized my concern about this approach a while ago by claiming that you can’t manage what you can’t understand.

Management should have learned by now that big problems often result from relatively small causes: a faulty sensor coupled with questionable software appears to have brought down two “state-of-the-art” airliners; a code snippet to improve emissions tests cost an automotive manufacturer some $20 Billion; a tiny broken valve spring lost many car races; and many IT projects stumbled because a component that no one knew about went out of support. Yup, it sucks, but failure simply refuses to respect our well-thought-out abstractions.

So, just looking at things from high-up doesn’t suffice when it comes to IT decision-making.

Building Bridges

How can we bring actual decision-making back into so-called decision meetings? The solution requires building a bridge from both ends in a classical Architect Elevator maneuver:

- Increase technical acumen at the top (management)

- Increase transparency from the bottom-up

Number 1 is essential, but such initiatives take time, so you’ll depend on building the bridge from the other end, also. Naturally, either approach requires some amount of goodwill from both sides.

Educate management

Regarding #1, I have long held a view that if you want to manage IT, you should understand IT: I am the CFO. I am not good with numbers. A great example of putting that insight into action was given by Oliver Baethe, CEO at Allianz: he sent all senior business leaders to IT Literacy training. Such an initiative not only improves decision-making, it also sends an important message that IT knowledge is critical to the business at all levels.

Alternatively, bringing more young people into existing teams can do wonders to challenge management’s existing way of thinking, akin to a “reverse mentoring” model. So, make sure you understand that your least experienced IT folks by far aren’t your least valuable ones!

Increase transparency

Not all learning has to occur in the classroom, though. When I present technical topics to senior management, I typically attempt to achieve two separate goals at the same time:

- Educate management, so they can understand and judge each option’s ramifications

- Solicit input so collectively we can make a better decision

Achieving both requires one to build material that includes a good ramp (see Chapter 16 - “Explaining Stuff”) for the audience. I find that explaining things well actually sharpens my own thinking, so it’s a useful exercise for me also. But I also find that not all teams are as forthcoming decision details.

The key ingredients into increasing transparency are confidence and integrity.

Teams that increase transparency need confidence and integrity: if you are confident that you have done your homework and have worked with high integrity, you wouldn’t have any problem creating transparency across all levels. So if you find your teams reluctant to share their decision-making, it may be indicative of a larger issue that you’ll need to tackle first.

Slow decision-making in a fast-moving world doesn’t work

When it comes to IT decision making, being detached from the technical reality isn’t the only problem. In an increasingly fast-moving world (see Chapter 31 “Economies of Speed”), slow decision-making is also poor decision-making. Running an important topic up the corporate food chain floor by floor takes time. Even if you get to a disciplined and well-thought-out decision, by the time you ran it through umpteen pre-committees, waited for the next steering meeting, failed to submit the slides the week before so someone can check the formatting (yup, happened to me), waited for the next steering, finally got approval, and waited for the meeting minutes, your decision may already be outdated. Again, it seems that the more important a decision is, the longer it takes – months aren’t uncommon. Sadly, more time spent doesn’t lead to better decisions (see Chapter 27 - Slow Chaos Isn’t Order).

In an ever-changing world snapshot decisions are inherently less meaningful, so your decisions need to account for technology and product evolution. Many organization’s inherent instinct to speed up decision-making by cutting corners aims exactly the other direction. Anyone who’s experienced (or suffered from) complex systems can see that less stringent decision making will increase entropy and complexity, which are sure to bog you down.

Write stuff down

A solid way to speed decision making is to replace slide presentations with documents (see Chapter 17 - “Writing for Busy People”). Documents scale better than slide decks because they are self-contained and can be widely distributed unlike slides that have to be presented to an audience by a person in real time.

Now, many organizations would claim that writing stuff down will actually take more time. I have two answers to this, which likely each warrant a separate post:

- You are optimizing locally, not globally, which makes you penny-wise but pound-foolish.

- If you know your stuff and have nothing to hide, writing it down won’t take you very long.

There’s a third argument: Amazon decides based on documents and practices it from the top down. It’d be hard to claim that they are moving slowly.

Sometimes, changing the way you work requires simple, but still very difficult changes.

More thoughts on transformation:

Make More Impact as an Architect

The Software Architect Elevator helps architects and IT professionals to take their role to the next level. By sharing the real-life journey of a chief architect, it shows how to influence organizations at the intersection of business and technology. Buy it on Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon Europe