Updated: Category: Strategy

A popular movie depicts the fierce rivalry between Ford and Ferrari during the 24 Hours of Le Mans race. Supposedly, the rivalry originated right at the top when Enzo Ferrari dismissed Ford’s take-over offer (over the long run that was likely a blessing for Ferrari, but let’s not spoil the drama). Enzo’s arrogant behavior apparently prompted Ford’s bid for revenge, in the form of the legendary GT40 car that beat Ferrari at the Le Mans race four times in a row. John Carrier turned the silverscreen drama into an insightful MIT article about the management lessons to be learned from the movie and the rivalry.

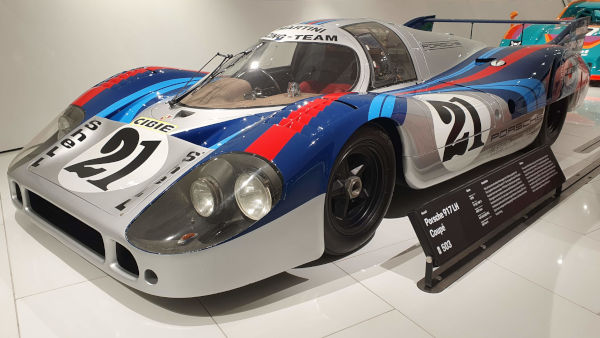

What the story (and the movie) celebrating American automotive engineering prowess fails to point out is that Porsche won the Le Mans during the subsequent years with its iconic 917 series, going on to win the race 19 times overall. Parent Volkswagen Group, which includes Audi, won 32 titles, far ahead of any other manufacturer.

I have been known to explain many things using car metaphors, so what better playground than derive some cultural insights from the Le Mans rivalry? I own an American, a German, and an Italian car, so I feel highly qualified to make unqualified statements and claim impartiality along the way! On top of all that, I spent good amounts of time working in the US, Germany, and Italy, so I am well-prepared to dish out evenly at all corporate cultures!

Warning: Parody Ahead

As with any story about history, countries, and cultures, please take this one with a few grains of salt. No offense is meant, but some might be had.

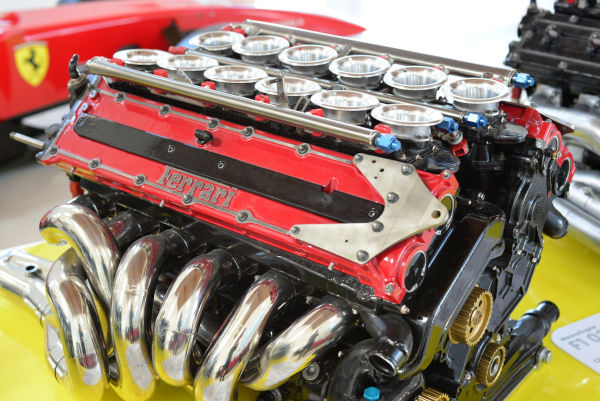

Italians don’t compete; they perform art

Ferrari and its red cars have been icons of any race league and childhood dream for more than half a century. In the Ferrari Museum in Modena you can admire not only the cars but also the engines: high-revving naturally aspirated V12s. Works of art! They don’t just win races, they also play music. That’s why Ferraris were late to adopt turbo chargers—who would want a Ferrari that sounds like a Subaru STI?! And they are still happily building combustion engine cars in 2024—I doubt we’ll see a small and round electric motor with few moving parts and a flat torque curve in the engine exhibit hall.

To Ferrari, it’s not just a race, it’s also an art exhibition and a harmonic ballet of piston movements. So, when Ford entered the Le Mans circuit with a serious car, Ferrari didn’t really feel the urge to compete. They kept playing music. Some Italian business meetings can feel similar: the subject matter might take a back seat to an elongated opera performance including a well-choreographed dance between the parties.

Americans love a good enemy

US automakers make some fun cars (I own a Cadillac and have always dreamt of owning a Corvette), but let’s be honest: American brands are rarely the stars at major international race events like F1 or Le Mans. Stateside fans appear to favor cars with large engines going around ovals, aided by smaller tires (not tyres) on the left half of the car. After all, all turns are left turns.

I had a blast at the NASCAR experience many years ago. But the giant steering wheel and long shifter made the car seem more like a truck than a race car. And before we got going, the instructor warned us that the brakes don’t work well.

Ford had been notably absent from Le Mans races, or at least the podium. Until Ferrari ticked them off. And they suddenly had an enemy to target. And it wasn’t just someone at Ferrari, it was the man himself! So, importantly, the enemy had a name and a face! And he’s harboring WMD’s—Weapons of Mechanical Dominance! That’s what awakened the fighting spirit: budget was available, motivation was high, consultants were hired (Carrol Shelby had a major hand in the development of the GT 40), and overtime was worked.

American business culture loves going to battle. In my consulting days we fought to gain ground, shot down arguments, and decimated the competition. On mellow days, we did sports: teeing off meetings, aiming for a home run, and trying not to be off base or drop the ball.

Germans make cars not movies

The GT40 won four times in a row. Just a few hours before its last victory in 1969, the outcome looked quite different, however. And that’s because two Porsche cars were in a significant lead. Porsche had built a new car that had started in pole position and was running several laps ahead. The now legendary Porsche 917 sported a flat-12 engine and many other innovations. It was also new, so both leading vehicles suddenly dropped out with gearbox issues in the last rounds, giving Ford the last center spot on the podium. Porsche was testing in production, so to speak, and a stroke of bad luck took out their redundancy. Still, an older Porsche 908 with a much smaller 3-liter engine gave the GT40 a run for its money to be beaten by just 120 meters thanks to skillful driving of the Ford team (Jacky Ickx would later drive for Porsche, securing some hands-down wins).

As you’d expect, Porsche soon worked out the kinks in the 917 and went on to win Le Mans twice in a row with its successors securing another 10 victories over the following years and 19 wins in total. Ford cleverly withdrew that same year, seeing quite clearly where things were headed for them. Quit while you’re ahead, as they say.

Alas, there’s no rivalry, no enemy, no drama, and no movie about Porsche. Just pure engineering perfection: air-cooled flat engines for a lower center of gravity, aerodynamic bodies for minimum drag but maximum down-pressure, space-frame chassis for light weight (42 kg!) and rigidity. And the crew celebrated with beer instead of Champagne and went right back to work.

Germans are no strangers to drama

Whereas the Germans seem to be as mechanically driven off the track as on, we can find a lot more emotion and drama in a rather unexpected corner: the board room and the shareholder conventions. Daimler’s love affair with Chrysler (or a shotgun wedding?) lasted a mere 9 years from honeymoon to bitter divorce. The 35-odd Billion which Chrysler lost in market value along the way was rather spectacular at the time. Nowadays, the likes of Jeff Bezos’ or Bill Gates’ shell out more for their private separations. The shareholder assembly summarized the drama as “all of you (the leadership) failed in the most irresponsible way”. Apparently Daimer threw in another $2 Billion as a parting gift: “ein Ende mit Schrecken ist besser als Schrecken ohne Ende” (a miserable ending is better than endless misery) is a well-known German proverb. Chrysler filed bankruptcy in 2009, so perhaps the Germans were onto something. And they were clever enough not to race a Chrysler, but instead built an awesome F1 team that scored in impressive 125 wins (the Italians are having the last laugh/cappucino here with 244 wins).

How to win a race

Perhaps the winning strategy is taking a bit from each culture. German engineering perfection, American grit, and a healthy dose of Italian emotion. Actually, my Cadillac is “American-Italian”, with the body built in Italy, flown over to the US, where it was mounted onto a US chassis. So, perhaps the rivalry ultimately subsided, even though the resulting car is better known for its Pininfarina-penned styling than its reliability.

Platforms appear to defy the laws of physics by boosting velocity and innovation via standardization and harmonization. Pulling this magic off is harder than it looks, so before you embark on your platform journey, equip yourself with this valuable guide from the Architect Elevator book series.

Grow Your Impact as an Architect

The Software Architect Elevator helps architects and IT professionals to take their role to the next level. By sharing the real-life journey of a chief architect, it shows how to influence organizations at the intersection of business and technology. Buy it on Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon Europe