Updated: Category: Architecture

Low-code/no-code application development is a hot topic these days and often viewed as the holy grail of software development, if we can still call it that after eliminating coding. Wikipedia lists over 20 vendors in this space, and the mandatory Gartner Quadrant counts 11, neatly grouped in three major clusters. Intent on not missing any trend I have also seen numerous tools and frameworks being re-labeled to use this moniker.

A major driver for the increased interest in such tools is the undeniable software engineer skills shortage (and associated personnel cost), ever-increasing pressure for faster application delivery, and perhaps a general dissatisfaction with IT departments’ delivery speed, or rather lack thereof. Lowering the bar for (routine) application development therefore seems a useful endeavor that can increase productivity and application quality, giving the citizen developer legitimacy along the way. On the other side of the coin stand IT departments looking to stamp out “shadow IT”, referring to application development inside business departments perhaps using non-sanctioned tools, which could pose a security or compliance risk plus a maintenance nightmare down the road (Gartner, ever-intent on keeping a neutral view, fittingly restricts the definition of citizen developer to “using tools that are not actively forbidden by IT or business units”).

Applying an architect’s mindset, this article dissects the buzzword and explores several techniques for reducing the amount of code to be written. So, the next time you look at a low-code proposal, you can ascertain whether the associated trade-offs match your needs.

The industry buzzword test

First off, it’s great to observe that the “low-code/no-code” buzzword passes my fundamental enterprise buzzword test:

It’s 1) a misnomer and 2) not really new.

What exactly constitutes code and a low amount thereof is subject to a fair amount of debate. Some low-code tools got cautious and state that “no programming” is required, but that might just lead us down another rabbit hole.

I wonder why we don’t call these platforms “high productivity” platforms—that’d be universally considered a good thing.

It’d also keep us out of the “what is code debate”, e.g. is an if statement code whereas a visual branch element isn’t?

Second, I have been impressed what my sister was able to accomplish with Microsoft Access without formal programming training–some 20 years ago. And the original Excel non-coders must be close to retiring now. Recent low-code vendors will quickly point out that those tools lacked central management and governance, which we might interpret as a form of acknowledgment coupled with a necessary definition of the term. As architects, we shun buzzwords anyhow, so we’ll look at what has changed and what remained the same.

Code is a liability, not an asset.

Having observed strong opinions on both sides of the low-code/no-code fence, I’ll reveal my main premise as a software engineer right up-front:

Less code is generally better—code is a liability.

Although source code is considered a major form of IP (intellectual property) for most modern organizations, writing more code isn’t necessarily better. More code might contain mode defects, require more maintenance, and undergo more testing. So, if we can achieve something in one line of code that’ll be better than having to come up with 10 lines of custom code.

Code Fear Not

As I highlighted in The Software Architect Elevator chapter “Code Fear Not!”, being panicked about code also won’t do much good. It appears too easy to exploit enterprise folks association of code with their many ailments–after all, isn’t that where most of the money goes and the bugs come from? As Russ Ackoff eloquently stated, managers are incurably susceptible to panacea peddlers. They are rooted in the belief that there are simple, if not simple-minded, solutions to even the most complex of problems. Coding is certainly a complex problem, and although we routinely work on, and make progress in, simplifying it, expecting a simple solution is likely to lead down the wrong path.

The reality is:

Coding is, and will remain for some time, the best way we have to express our thoughts such that a machine can execute them. Coding gives you the power to differentiate in the marketplace and to do things that no framework or packaged software foresaw.

Hastened efforts to replace coding with configuration have led to “configuration that’s just programming, albeit in a poorly designed language without useful tooling or documentation”, as I summarized in The Software Architect Elevator. I am therefore intent on balancing the discussion such that eliminating coding across the board shouldn’t be the goal. Making coding more efficient, safer, and available to a wider audience are all noble goals that we should pursue.

9 Ways to Lessen Your Code

Many folks are looking to reduce the amount of code we need to write, and rightly so. Some approaches are more promising than others, so as architects we are compelled to create list of possible approaches and evaluate their respective trade-offs.

9. Clever Code

Architects are in the business of balancing trade-offs, so let’s start by tempering the quest for less code with an important corollary:

More clear code is better than less unclear code.

Anyone who has written software on a team surely has come across code written by a fellow engineer who had a particular interpretation of “low-code”: being able to squeeze complex logic into a single line through clever tricks (this guy surely has). The typical result is one line of code that takes more effort to understand and maintain than the 10 lines it replaced.

So, let’s disqualify this attempt at low-code right away. Using programming language features and libraries is highly encouraged, but somewhere there’s a subtle but critical line between “succinct” and “clever”, the latter being an anti-pattern or at least a warning signal.

Thus we stumble over the first issue in the “low-code” moniker - how do we count code so that we can honestly claim that something is low in code? This’ll be a more difficult question to answer than food being low in calories (but even there we managed to discern “empty” calories). Given that the amount of liability related to code a function of our ability to understand, debug, and maintain it, I’ll propose the following approach to measuring code:

We shouldn’t count the amount of code in lines but in cognitive load.

Following this definition, the single clever can no longer claim to be low code because it carries the same or an even higher cognitive load. I realize that one programmer’s high cognitive load is another’s morning warm-up, so we’ll let this stand as a qualitative metric. Just for kicks, here’s a Python one-liner that might be considered high in cognitive load (I am actually a big fan of lambda expressions and map/reduce functions):

(lambda n:reduce(lambda x,n:[x[1],x[0]+x[1]], range(n-1),[0,1])[0])(5)

8. Sleight of Hand / Relabeling

With tens or hundreds of millions of marketing budgets behind a new buzzword one should expect a few free loaders who purport their system to suddenly be in the running. You can’t entirely blame them. So, we might just offering them what they want.

When claiming to turn something into “not code” one has to have a definition of what makes something code. Wikipedia, always a good starting point, defines code as either a sequence or a set of instructions. It does not specify the syntax of the instructions, so changing something from free-text format to a structured format is just a sleight of hand and wont increase your productivity. Given the popularity of converting things into JSON or YAML, I have voiced my opinions on this topic before:

Wrapping something into JSON syntax doesn’t provide any abstraction whatsoever. Often it achieves the opposite: creating some magic settings that are utterly meaningless without a full understanding of the machinery underneath. Twitter

This is not low-code, it’s just a really, really poor syntax for code:

Condition:

Operator: "[less or equal]"

Parameters:

- Type: Variable

Value: Age

- Type: Number

Value: "40"

Action: DoSomething

7. Configuration

The next well-known technique of reducing the amount of code one needs to write is through configuration. The basic idea of configuration is that you’ll code the algorithm inside your software, allowing users to specify parameters afterwards. The basic ideas is to implement useful variability points, ostensibly without the risk of coding. The previous code snippet might be reduced to:

AgeThreshold: 40

Although appearing harmless at first, the perils of this approach have been around long enough that I blogged about it back in 2005, coming up with the following piece of advice:

If changing settings can break your application, you better consider that coding.

The chapter Code Fear Not in The Software Architect Elevator illustrates the slippery slope between configuration and coding. Just imagine a configuration setting that takes a numeric parameter to determine a major business process, for example, a purchase threshold for a manual review or a credit check. A business user sets that number, unaware that it’s to be specified in cents, not whole Dollars. Every order is now flagged for an additional review, grinding your business to a halt. Specifying a value isn’t per definition safe.

The biggest challenges with configuration that I have observed are:

- It required the system designer to have anticipated your use case. Unless the designer is a clairvoyant or your needs are 100% average, this is a tricky proposition, especially in today’s unpredictable times.

- It requires knowledge of the internal workings of the system, generally without being able to have an actual look. Configuring software isn’t like setting cruise control on your car–parameters will impact complex logic.

- Because it’s assumed to be “safe”, configuration often lacks the same safety nets that have become commonplace when making code changes, for example, syntax highlighting, editor support, version control, code reviews, and automated tests.

For vivid examples of the perils of configuration changes, have a look at major cloud outages , like this one (pick your favorite, or perhaps least favorite vendor) that summarizes:

“In essence, the root cause of Sunday’s disruption was a configuration change that was intended for a small number of servers in a single region. The configuration was incorrectly applied to a larger number of servers across several neighboring regions…”

6. Doodleware

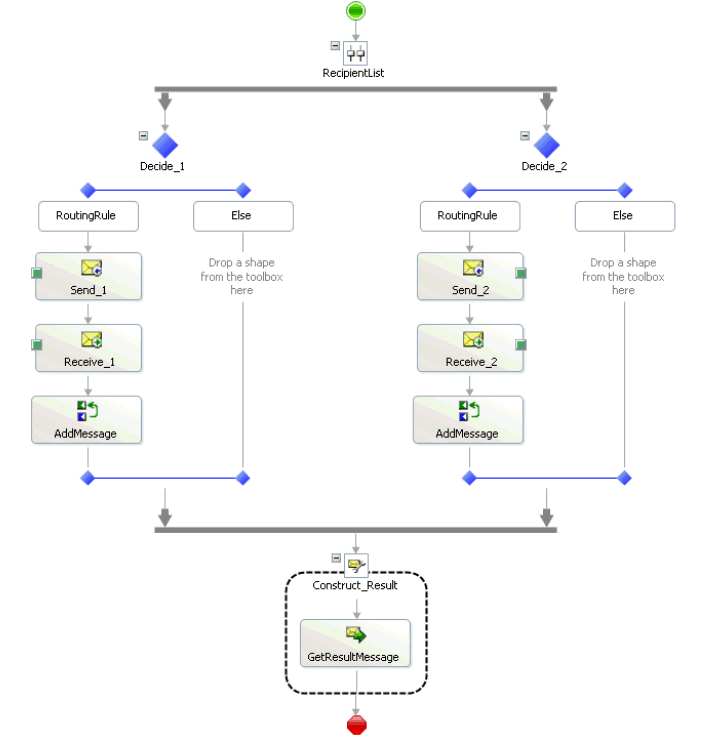

Code is text. That should mean that graphical environments are low-code, right? Digging up my blog post from 2003, let us be reminded that visual representations work very well for a subclass of programming models, for example workflows or user interface designs. They, do, however, generally make for poor programming environments because they don’t scale well and don’t support basic operations like diff. Also, most people type much faster than they can draw with the mouse. I have had early exposure to visual tools as I started my career around the 4GL wave, building large business applications in PowerBuilder, and having worked extensively with integration tools (e.g. my paper on Integration Patterns with BizTalk contains many screen shots of the visual environment):

I actually have some good experiences with visual tools. For example, my recent adventures in serverless-land included defining orchestrations, in this case using AWS Step Functions. Being able to do so in the Workflow Studio as opposed to having to write it in the Amazon States Language definitely lowered the learning curve. As in most cases, for a solution that’s bigger than my simple test application, I’d likely switch back to code (luckily Workflow Studio saves as editable code). Another nice example would be Android App Inventor, co-created by my Google office mate Mark Friedman, or the popular Scratch development environment.

At the same time, we must remember that visual tools, endearingly called “Doodleware”, can help us with the syntax, but they don’t make the cognitive load of the underlying model disappear. For example, even when dragging and dropping states around the screen, you need to understand the constructs you are using, the ups and downs of parallel execution, state management, run-time limitations, asynchronous completions, and many more. Just converting something into a diagram doesn’t immediately make it suitable for non-programmers.

Lastly, while diagrams are a great way for humans to understand complex structures, we tend to type much faster than we can shuffle things around the screen with a mouse, just to double-click on one box to fill in a tad bit of text. So, most of the time we find that:

Generating diagrams from code outperforms generating code from diagrams

5. Libraries & Prebuilt Components

After tackling code-reduction techniques that stayed at the surface, so to speak, let’s remember that most code that we write is intended to reduce the amount of other code we write. For example, hardly any developer would write their own strlen function or length method. That’s what we have libraries for. Libraries range from a collection of convenience methods like strlen to full-on frameworks like Spring Boot that makes building a running web service a matter of a few lines of code.

Perhaps the most successful collection of pre-built components was Microsoft’s VBX ecosystem, later replaced by OCX. I remember receiving catalogs (yes, it’s some time ago) with literally hundreds of pre-built components that allowed you to rapidly compose Windows applications. Many components were UI elements like data grids and text editors while others would provide common functionality like compressing / decompressing data. ComponentSource lists 873 presentation layer components for .NET. I’d consider this ecosystem the first truly successful low-code environment and have seen “citizen developers” create business applications in short amounts of time.

While components and libraries reduce the amount of code you need to write at design time, your application can also call third-party services at run-time. Cloud platforms have removed much of the friction from this form of development. For example, you can add checkout and payment functionality to your web application with just a few lines of code using popular payment services like Stripe. Using third party services is nothing new in software development but making integration this simple enables a new style of application composition. Think of it as the new generation of VBX controls.

The amount of code you write is already minuscule compared to the total amount of code in the system

4. Code Generation

One drawback of third-party libraries and components is that they are pre-built. If they provide the functionality you need, you can drastically reduce your development effort. However, if you need something slightly different, you might need to start from scratch.

Another technique to reduce the amount of code you need to write is to generate code based on input given in a higher-level abstraction. In a way every compiler is a (machine) code generation tool, allowing us to code at a higher level of abstraction while giving the machine a native format to execute. Code generation tools have seen various ups-and-downs, generally suffering from poor debuggability: defects in generated code often lead to obscure error messages and can’t be fixed in situ but have to be reverse-engineered into the actual source code. Mainstream compilers address (or at least ameliorate) these issues with symbol tables and stack traces, mechanisms that are absent in most higher-level “low-code” tools that rely on code generation. As language design progressed, many code generation tools were replaced by domain-specific languages that do not generate intermediate-level code (see #3).

Code generation can work well when the source isn’t code but another structure like a database schema. Based on the existing structures, relationships, and data types, a generator can generate code for a complete user interface that includes searches and updates. The downside is that the generated UIs generally have limited concern for usability.

I recently had to report travel days in a web-based app developed in a low-code tool. The UI was cumbersome because it forced me to select individual dates, enter detail data below and “save”. Apparently the UI was anchored to a simple table / record / detail / save paradigm. Surely a better UI could have been built in the same tool - with custom code…

A welcome form of code generation have been smart IDEs like IntelliJ IDEA that generate boilerplate code like getter and setter methods from keyboard shortcuts. Code generation in this case is no longer an additional step but a convenience during the coding process. GitHub Copilot takes this idea a whole level further. The only downside, perhaps, would be that the generated code becomes part of the source code, so you reduce the amount of code you write but perhaps not the amount of code you have.

3. Domain Language Abstractions

Many applications are written using general-purpose programming languages like Java, GoLang, or JavaScript (Wikipedia has a list). Those languages’ flexibility is offset by their verbosity. Specifically, most general-purpose languages exhibit a major gap between the business logic and the written code. The code will be littered with keywords and constructs such as classes, methods, promises, futures, threads, exceptions, and much more, making it difficult to see the actual behavior of the system, especially for non-programmers. Programmers have been using techniques like abstraction, common base classes, or annotations to make the code more expressive and less “noisy”, with Domain-Driven Design or POJO (Plain Old Java Objects) approaches having been a major guiding factor.

Domain Languages have one major advantage: they don’t need to solve all problems but only those within a specific domain. By choosing a narrow domain, you can reduce the amount of flexibility you need and therefore the amount of code you have to write. A domain here can refer to a business domain or a technical domain. For example, Spring Boot includes a simple technical domain language for serving Web requests with Java methods:

@GetMapping("/")

public String index() {

return "Greetings!";

}

The GetMapping annotation specifies that a GET on this endpoint for the root element will be handled by this method. Without the underlying framework, this functionality could easily require hundreds of lines of code, so it’d be fair to call this a “low-code” approach for the technical domain of web requests.

Not all domain languages have to extend a primary (usually object-oriented) language. Many business or scientific domains have used specific languages for a long time, whether it’s VisiCalc or Excel functions, MATLAB, or Hypercard. Also, domains like workflow processing lend themselves to compact expression in custom languages, for example implemented as the Amazon States Language or Google Cloud Workflows Syntax as modern examples.

Embedding domain languages in other languages allow us to drastically use the amount of code needed as for each aspect there’s the ideal language. It does, however, lead to what I call polyglot low-code: you might be writing very few lines of code but a single line may combine multiple languages, each with their own functions and syntax. For example, the following line combines CloudFormation functions, EventBridge patterns, and string literals defined by both the run-time platform and the application:

functionArn: [{ prefix: !Sub 'arn:aws:lambda:${AWS::Region}:${AWS::AccountId}:function:BankSns2' }]

It’s better than #9 but still means that the cognitive load per line increases substantially.

2. Declarative Programming

Many of the effective domain languages are declarative. For example, workflow definitions contain a definition of steps but often don’t include explicit invocations from one step to another–that’s left to the run-time platform to handle. Declaring dependencies instead of execution order is at least as old as make, which dates back to 1976 and as fresh as Apache Airflow, which uses an OO language (Python) to declare task dependencies.

Declarative languages generally confer more aspects, e.g. sequencing of events or state management, to the underlying run-time and thus can make for more compact code. However, reducing the amount of code is perhaps not the primary goal but a side-effect of a more expressive programming model for this subset of tasks.

1. Assumptions / Defaults

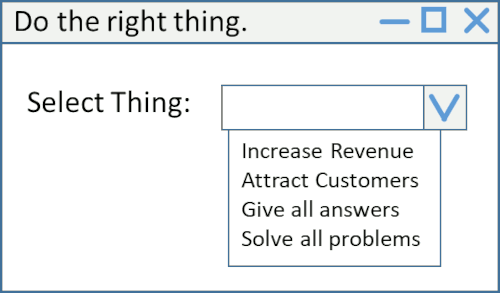

The natural question is how far you can push the abstractions with domain languages, libraries, code generation, and declarative programming approaches. As an extreme example, I tend to present the following low-code environment:

doTheRightThing(enum thing)

The no-code variant would look like this:

Wouldn’t such a function be awesome? Yes, it would, until you need a thing that’s not in the enum. Although an intentionally silly example, it highlights the trade-offs we make when we further look to reduce code:

- The solution pretends to have anticipated all possible use cases

- It has a “cliff shaped utility curve”: you’re fine while you’re in the solution’s sweet spot but outside the abyss awaits you

There’s obviously an optimum along the spectrum and a point where things decline. Anticipating all needs appears ill-advised in today’s unpredictable and fast-moving world, so workable low-code solutions need to maintain a suitable amount of flexibility and gentle slopes on the side, coming back to the old adage to “make simple things simple and complex ones possible (with reasonable effort)” by Alan Kay (parentheses by me).

Defaults that can be overridden can be a viable way to reduce coding without giving up flexibility.

Defaults must be natural and intuitive. If someone has to lookup a default to understand the system behavior, then specifying the value would have been equally efficient or even more so.

We have to recall that it’s not so much the lines of code that we are looking to shrink but the cognitive load of the solution and the effort it took, both of which are closely related.

Where are we headed?

Apparently, the desire to reduce coding effort and volume has been without for some time. On a recent Twitter thread, someone claimed that “everything besides assembly language is low-code” and they are right: we would not even be close to being able to build today’s applications if we weren’t operating on a giant base platform of libraries and services, supported by high-level constructs and abstractions.

At the same time, the low-code, no-code (“loconoco”) buzzword is seeing a definite boost in recent years.

Smaller, More Useful Apps, Faster

As hinted at the beginning, today’s fast-paced environment requires shorter software delivery cycles–the days of 24 month IT projects are, luckily, largely gone. There’s a bigger pressure for applications to delivery business value sooner, so bringing software delivery closer to the business is surely a good thing.

A trend for organizations to become more data-oriented and take better advantage of analytics and machine learning capabilities also puts custom solutions into more users’ hands. We moved from data warehouses, operated by people in white lab coats, to data lakes, data marts, lakehouses and democratized data meshes. Empowering end users and taking the mystique out of “coding” a solution is therefore a positive trend.

More Devices, More Complexity

Modern solutions are immensely powerful and complex at the same time. We can access our applications from anywhere at any time from almost any device, with access protected by biometric two-factor authentication and intrusion prevention, operating on globally distributed data stores across multiple availability zones, and auto-scaling as required.

Given the widespread shortage in software engineers, reducing code, or rather complexity, has to be a major vector to keep the systems we built manageable and to have enough folks at hand to build them.

Low-Ops/No-Ops

Besides all the benefits of lowering the amount of code we need to write, we shouldn’t assume that writing code is where all the effort (and all the money) goes. For most applications, that’d be maintenance and operations. We should therefore equally welcome successful efforts to reduce operational effort like most SaaS products do. In fact, most low-code tools on the market that target business users are also virtually “no ops” tools. Perhaps that slogan isn’t as catchy as “no code” but it’s equally important.

Evaluating Low-code tools

When looking at low-code tools (which you likely are if you’re in an enterprise), I recommend applying the following tests:

- Identify which mechanisms were used to reduce the amount of code. The list above may be a useful starting point—there’s no magic in software; you need to know what techniques were chosen and which trade-offs they imply (Microsoft for example gets bonus points for openly sharing some of the trade-offs)

- Carefully consider whether the remaining “low code” is also “low cognitive load” or a jumble of custom syntax embedded in double quotes in a YAML file.

- Examine how the solution can evolve over time. Is there version control? Can you revert to a prior version if something breaks? How well will the tool scale beyond demo-scope? For example, most Doodleware looks great while everything fits on one screen but grows cumbersome quickly after that.

- Consider the unhappy path: are error messages clear or do they leak lower-level abstractions? What happens when you make a mistake? How can you debug?

For the last two points, my favorite vendor-demo exercises (described in The Software Architect Elevator) are:

1) Include an error (typo, wrong field name) in user-provided “code”

2) Ask the vendor to leave the room, make some random changes to the app to break it, and ask the vendor to debug

I’d add a third, slightly friendlier one:

3) Rather than have the vendor build a solution for you, ask to be at the keyboard and build yourself. Measure how much help you need.

As architect, we love progress, but we don’t take buzzwords for gospel. Let me know what experience you had with low-code/no-code tools (social media links below).

Make More Impact as an Architect

The Software Architect Elevator helps architects and IT professionals to take their role to the next level. By sharing the real-life journey of a chief architect, it shows how to influence organizations at the intersection of business and technology. Buy it on Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon Europe